Rumors

Betting against the US economy is foolish — taking it for granted even more so.

“Rumors of my death have been greatly exaggerated,” said Mark Twain. The same holds for the US economy, yet again.

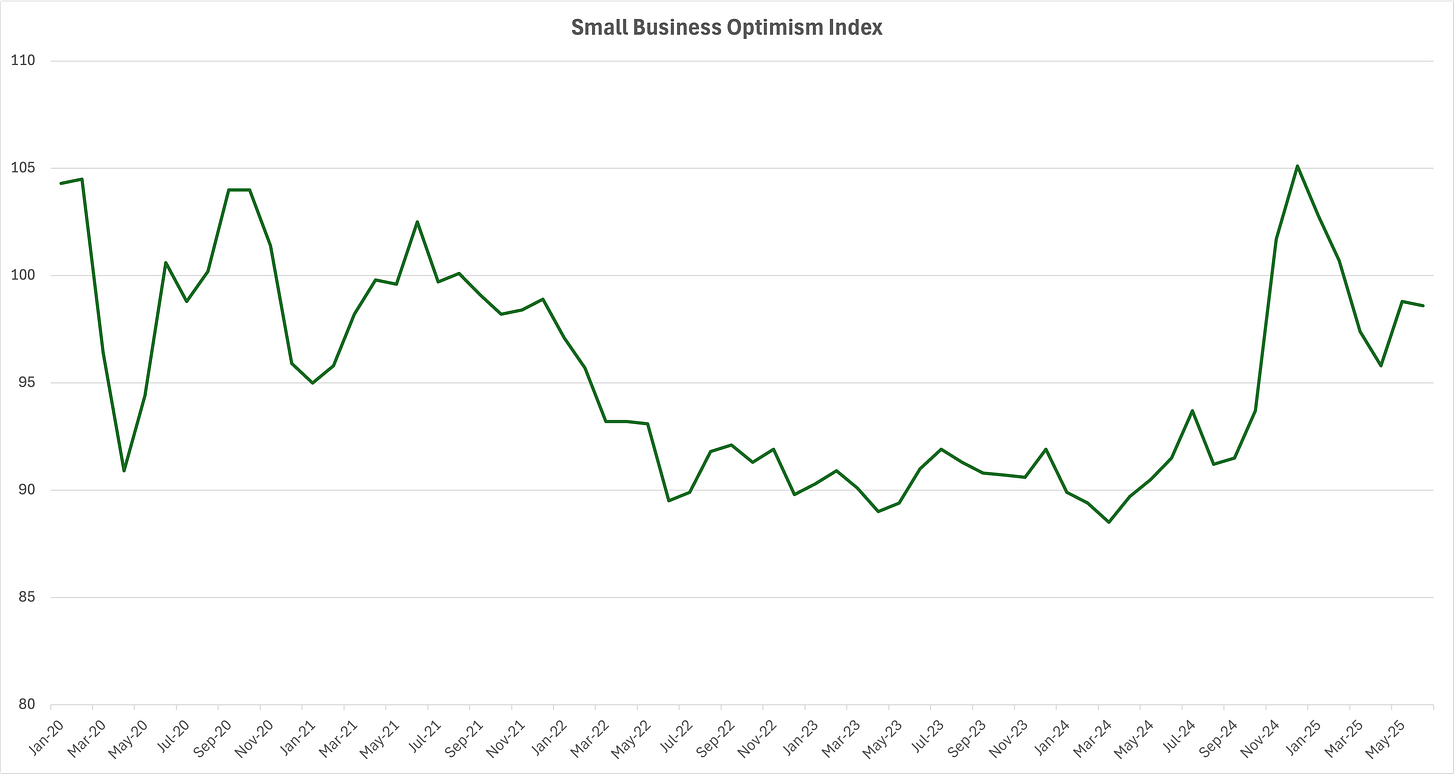

After President Trump won a second term, economic expectations were upbeat — with the predictable partisan divide. Small business optimism surged, much as after Trump’s 2016 victory. Then came “Liberation Day,” threatening all trading partners with exorbitant tariffs based on economically illitterate calculations. Everyone predicted dire consequences, equity markets collapsed, and economists rushed to boost their recession probabilities.

(Goldman Sachs economists upped their recession forecast to 65%, but just two hours later they revised it down to 45% as Trump announced a 90-day grace period — making it perhaps the shortest-lived economic forecast ever. They have now reduced it further to 30%. I think recession forecasts are useless at the best of times — pulled out of shaky statistical models. But with the current level of policy uncertainty they do make for great entertainment.)

Assorted analysts and pundits declared the end of global dominance for the US, the US dollar and US Treasuries. Canada’s Mark Carney and Germany’s Friederich Merz were nominated as new leaders of the free world and Carney embraced the prospect with combative statements.

Oh well.

We have not seen much ex-US leadership recently, and the strikes on Iran’s nuclear facilities reminded everyone that global leadership requires hard power and the willingness to use it.

It just keeps going

US economic developments have been reassuring: Job creation exceeds what’s needed to maintain full employment, taking into account new immigration restrictions. Economic activity has proved resilient. Most sentiment surveys have weakened, but small business confidence is still well above the average of the past three years — and small businesses account for about half of the US workforce and over 40% of GDP.

Source: NFIB

Corporates are cautious, but not frozen in fear. They have slowed capex plans, but are not downsizing. Tariff revenues have increased — bringing in about $100 billion so far this year, over twice the same period last year — but inflation has not rebounded. Oh, and US equity markets have jumped to new highs.

What should we make of the dissonance between this macro data and the panic of three months ago?

There have been some positive developments, some fears were exaggerated in the first place, and corporate leaders have so far taken a constructive approach to policy uncertainty. But we are underestimating the long-term risks.

In the long run we are all insolvent

The good news is the approval of the new budget plan. Here the ‘Big, Beautiful Bill’ rhetoric meets the familiar cry of ‘we’re all going to die’. Harvard’s Larry Summers blasted the bill, claiming it imposes “the biggest cut in the American safety net in history,” and will cause 100,000 deaths in the next ten years through tighter Medicaid requirements. At the same time, critics argue that the bill is fiscally irresponsible because it will leave us with large deficits for years to come.

It’s hard to cut through the hysteria, but here’s my two cents:

We do face a parlous fiscal situation — partly because we ran a 6% of GDP average fiscal deficit over the past three years, after the economy had rebounded handsomely from the Covid shutdowns. I would much prefer to see some fiscal tightening, but the Trump administration decided to prioritize a growth-supportive fiscal stance centered on making permanent the current (relatively) low tax rates. This, lest we forget, is what American voters chose last November.

To limit the fiscal gap, the government wanted some expenditure cuts. Rightly so, in my view. As I’ve argued in a previous blog, the US fiscal deterioration has been driven by rising expenditures — non-interest expenditures last year were 5% of GDP higher than when Bill Clinton left office, a 30% increase as a share of the economy.

With non-defense discretionary spending at only 14% of total, cuts need to focus on entitlements, and since Medicaid spending rose by a remarkable 50% between 2019 and 2024, it was a natural candidate. The requirement that able-bodied adults should work or perform community service to maintain eligibility does not sound unreasonable, and is supported by two thirds of Americans, according to a June survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation1 (but see the footnote for why I distrust surveys almost as much as recession probability models…)

In the short run, the BBB is positive for growth. And in the long run we are all insolvent, to paraphrase Keynes.

Tariffs, the most tiresome word…

Inflation concerns were always overblown. Raising a tariff causes a one-off increase in the relative price of the affected goods, not a permanent acceleration in all prices. Higher tariffs are impacting selected CPI components, and will continue to do so (see this post by Gerwin Bell), but are not disrupting the painfully slow ongoing disinflation.

Remember though that tariffs are a tax and not, as the current administration would have us believe, another form of exorbitant privilege the US can impose on foreign countries. This has two implications. First, that tariffs will help close the fiscal deficit. An across-the-board 12% levy on all imported goods would raise more than $300 billion additional revenue every year (above the $80 billion average of the last five years). That’s $3 trillion over ten years, which would cover almost the entire “cost” of the BBB as estimated by the CBO. Second, like any tax tariffs have a negative impact on growth and will therefore limit the fiscal stimulus of the bill.

Unknowable unknowns

The US economy is most likely to keep expanding at a solid pace this year… unless President Trump torpedoes it. Financial investors have digested the idea that tariffs will settle somewhere in a 10-15% range, and the real economy could adjust to it, with some pain. Tariffs of 25-50% however would be much more disruptive — and unfortunately we can’t rule them out.

Tariffs have become an unknowable unknown, given Trump’s capricious pronouncements. This kind of uncertainty is extremely hard to deal with. For now corporate leaders have taken a constructive attitude, but at some point they might throw in the towel and go into full cost-cutting mode.

Dangerous temptations

The US economy is a formidable force. It has a remarkable ability to absorb all kinds of blows, adapt and keep growing. Economists have been predicting a recession since the Fed started raising interest rates in 2022; yet the US economy expanded by an average rate of 2.7% over the past three years, and keeps going.

Unfortunately, there is a natural but dangerous temptation to take this strength for granted; this entitled mentality opens the way to policy decisions that risk undermining the economy’s resilience over the long term:

First and most obvious, unsustainable fiscal policy. Unless we get deficits under control, sooner or later they will translate into some combination of higher taxes, higher inflation, and higher interest rates.

Second, immigration. The Biden administration’s open borders policy was reckless, but now we’ve jumped to the opposite extreme, even discouraging the flow of the world’s best and brightest into US universities. This will sabotage human capital, innovation and growth — unless we can converge back to a sensible approach.

Third, trade and tariffs. We have probably overestimated the benefits of globalization — and certainly underestimated the risks. The global economy might even take in stride an increase in US tariffs to an average of about 10-15%. But businesses cannot live indefinitely with the fear of 20-50% levies falling at random on their key inputs or on their own products. And higher tariffs will almost certainly create a complex web of loopholes and exceptions — a classic source of inefficiency.

Betting against the US economy is foolish — taking it for granted even more so.

The Kaiser Family Foundation is vehemently opposed to the eligibility requirement. In the third bullet point of the article linked above, they (1) reluctantly admit that 68% of Americans support the Medicaid work requirements in the BBB; but (2) note that support drops to 35% when supporters are told that “most people on Medicaid are already working and that many would be at risk of losing coverage because of difficulty completing paperwork to prove their eligibility,” as the KFF maintains; and (3) support rises to 79% “if opponents hear the argument that imposing these requirements could save money and help fund Medicaid for the elderly, people with disabilities and low-income children,” something the KFF deems false. Another reminder that how you phrase the question often helps shape the answer.

I would agree that most of the serious damage that is being done by the Trump administration to the US economy will accrue only over the medium term, and there is too much focus on short-term effects. At the same time, the economic policy mix shaping up comes across as uniquely misguided: An abrupt and capricious switch to non-cooperative trade policies; a sudden contraction in net immigration; 10 years of war-time high fiscal deficits; and, finally, installing a Turkish-type monetary policy of high inflation at the Fed.

Great piece Marco. As you know on tariffs I maintain that between three-months postponement and other tricks, the effective tariffs imposed by countries will be eventually practically insignificant (remember the ‘un fiorino’ scene in the Italian movie ‘non ci resta che piangere’?)