Blue, Red And Bankrupt

Anatomy Of A Fiscal Meltdown

This is an almost irrelevant article.

In the comments section of my previous post, Larry Hatheway and I got into a sparkling debate on whether Democrats or Republicans have a better record on fiscal responsibility. Larry argued that Republican fiscal responsibility is a myth that needs debunking. Other readers agreed with him that Democrats have been far more fiscally responsible. I disagreed. But after looking at the numbers again, I think we are all wrong.

I thought it might be worth sharing the data and a few thoughts, to help separate myth from reality. You can draw your own conclusions. Ultimately, it does not matter. Not anymore.

We’ve had one true champion of fiscal responsibility, and that was Bill Clinton — a Democrat. But, even with him, the data show no difference in fiscal responsibility between Republicans and Democrats, in my view.

The data do show, however, a definite turn towards fiscal recklessness over the past twelve years, and it’s bipartisan.

Let’s take a look.

Dear Prudence

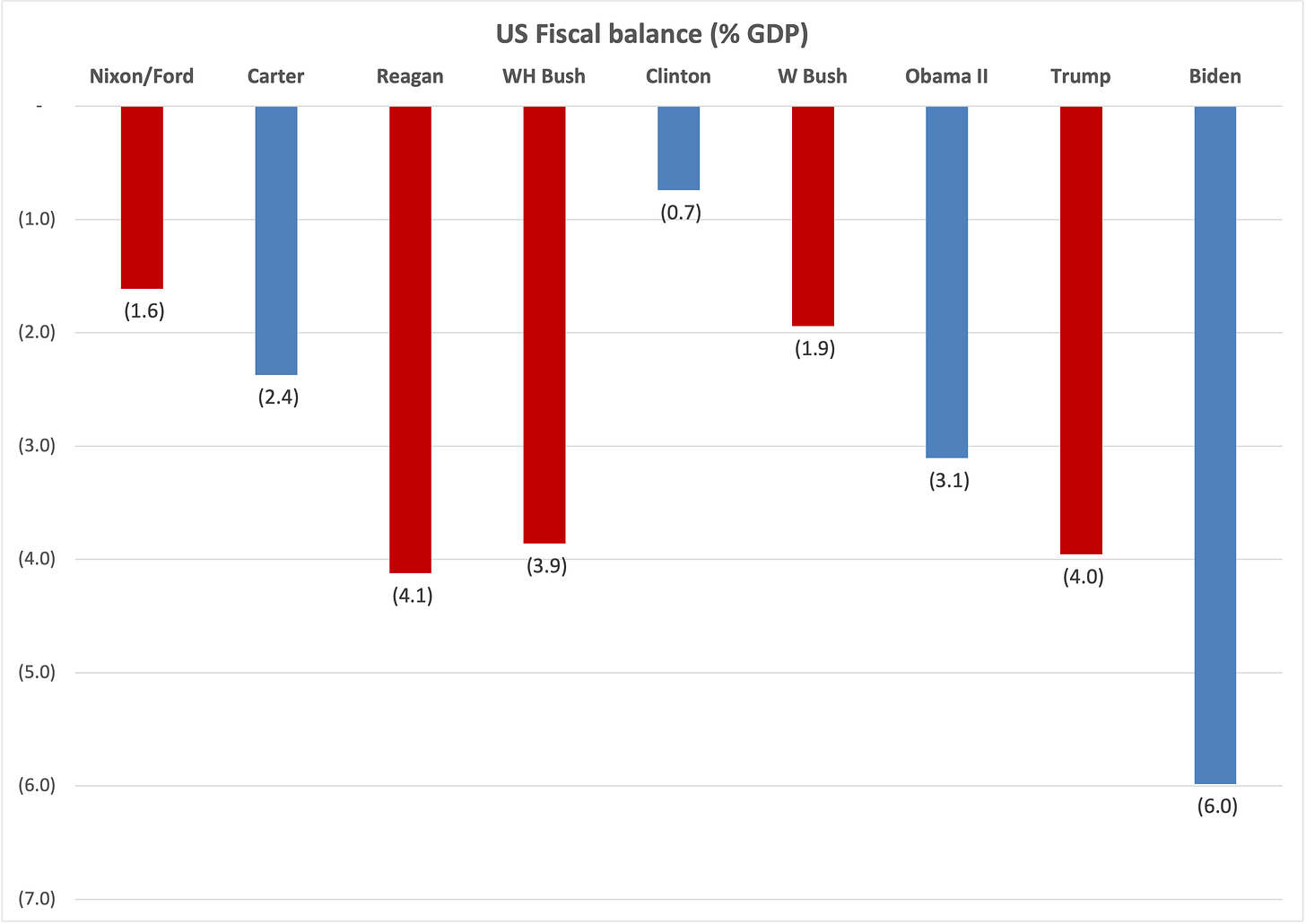

What’s the right way to assess an administration’s fiscal prudence? In first approximation, for me it’s the average fiscal balance over its tenure. It tells us to what extent the government has been living beyond its means, borrowing and adding to the debt. The chart below shows the average balance under the last nine administrations, starting with Nixon/Ford and ending with Biden.

The Global Financial Crisis and the Covid shutdowns triggered massive fiscal expansions, and it would be unfair to let those skew the picture. Therefore, I am leaving out Obama’s first term, dominated by the giant fiscal stimulus deployed to cushion the GFC blow (with an average fiscal deficit of 8.4% of GDP); I am also leaving out the last year of Trump I, and the first year of Biden, with a cumulative deficit of 27% of GDP.

Source: Congressional Budget Office; JustThink calculations. Excludes 2009-12 (GFC), 2020, and 2021 (Covid).

Two things jump out from the chart:

Clinton’s exceptionalism.

The subsequent slide towards looser and looser fiscal policy.

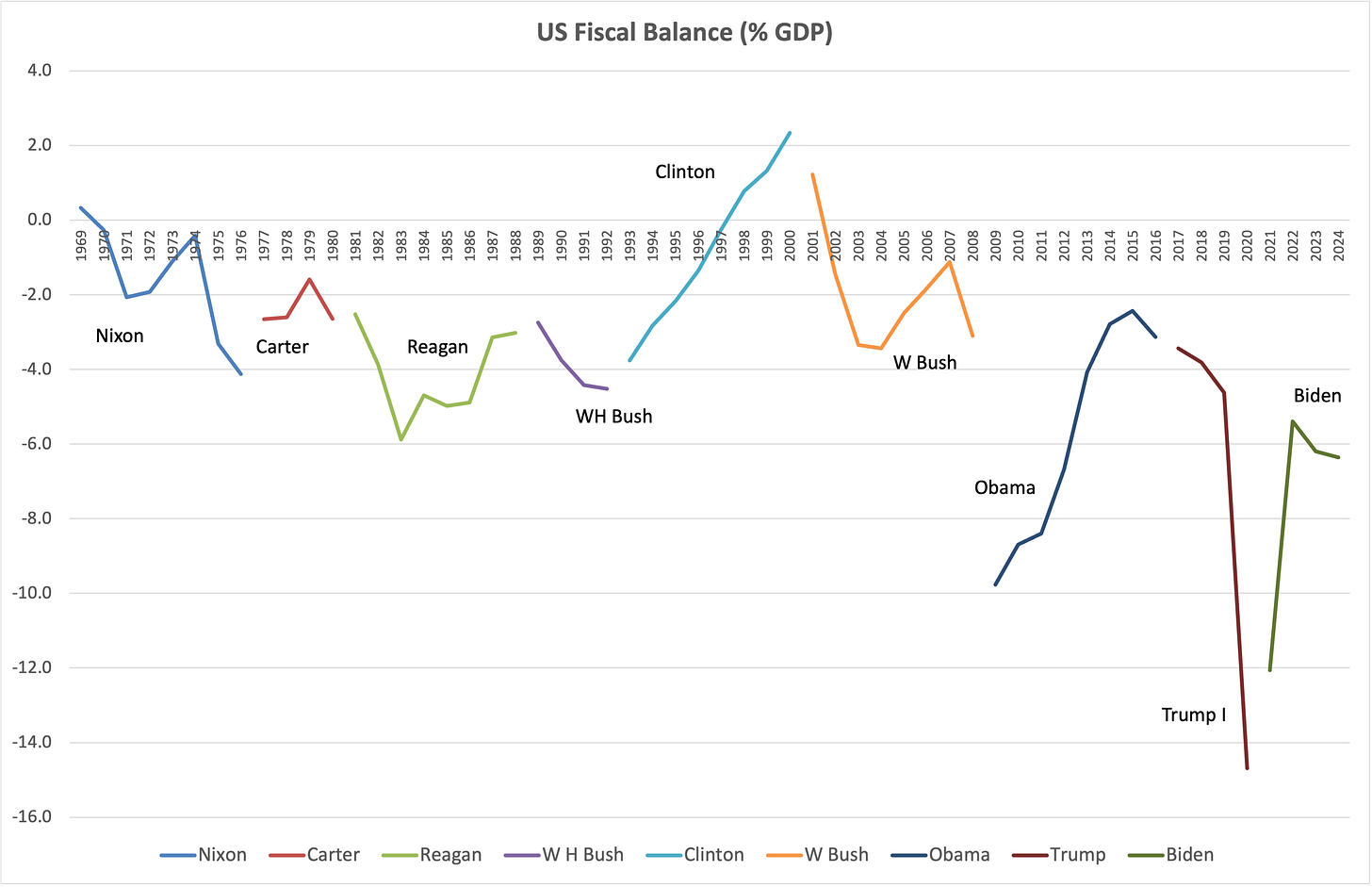

Larry and others argue term averages are misleading, and we should instead look at the trend over the tenure of a President: did he improve the fiscal accounts and leave them stronger than he found them? It’s a fair argument. Based on this, they say that there have been three multi-year fiscal consolidation episodes, all under Democratic administrations: Carter, Clinton and Obama. Let’s take a look:

Source: Congressional Budget Office

Clinton was a hero — no argument there.

Carter? I’m sorry, but no. The deficit remained stable during his tenure. He did reduce it from 1975-76, when under Ford it had risen to 3% and then 4%. But prior to that Nixon had run a very tight policy, so that the average deficit under Carter (2.4% of GDP) was 50% larger than under Nixon/Ford (1.6%).

Obama? Again, I disagree. Of course I don’t blame Obama for the massive fiscal stimulus of 2009 — quite the opposite. But neither do I give him special credit for bringing the deficit back down during a string of years when GDP growth averaged a healthy 2.3%, the Fed ran a phenomenally expansionary monetary policy, and interest rates were as low as they could be.

Having taken out the outliers, the fiscal deficit averaged 3.1% of GDP under Republican administrations. And under Democratic administrations? Exactly the same 3.1% of GDP. (If you don’t leave out the outliers, it’s 3.2% under Republicans and 3.8% under Democrats).

Against your interest

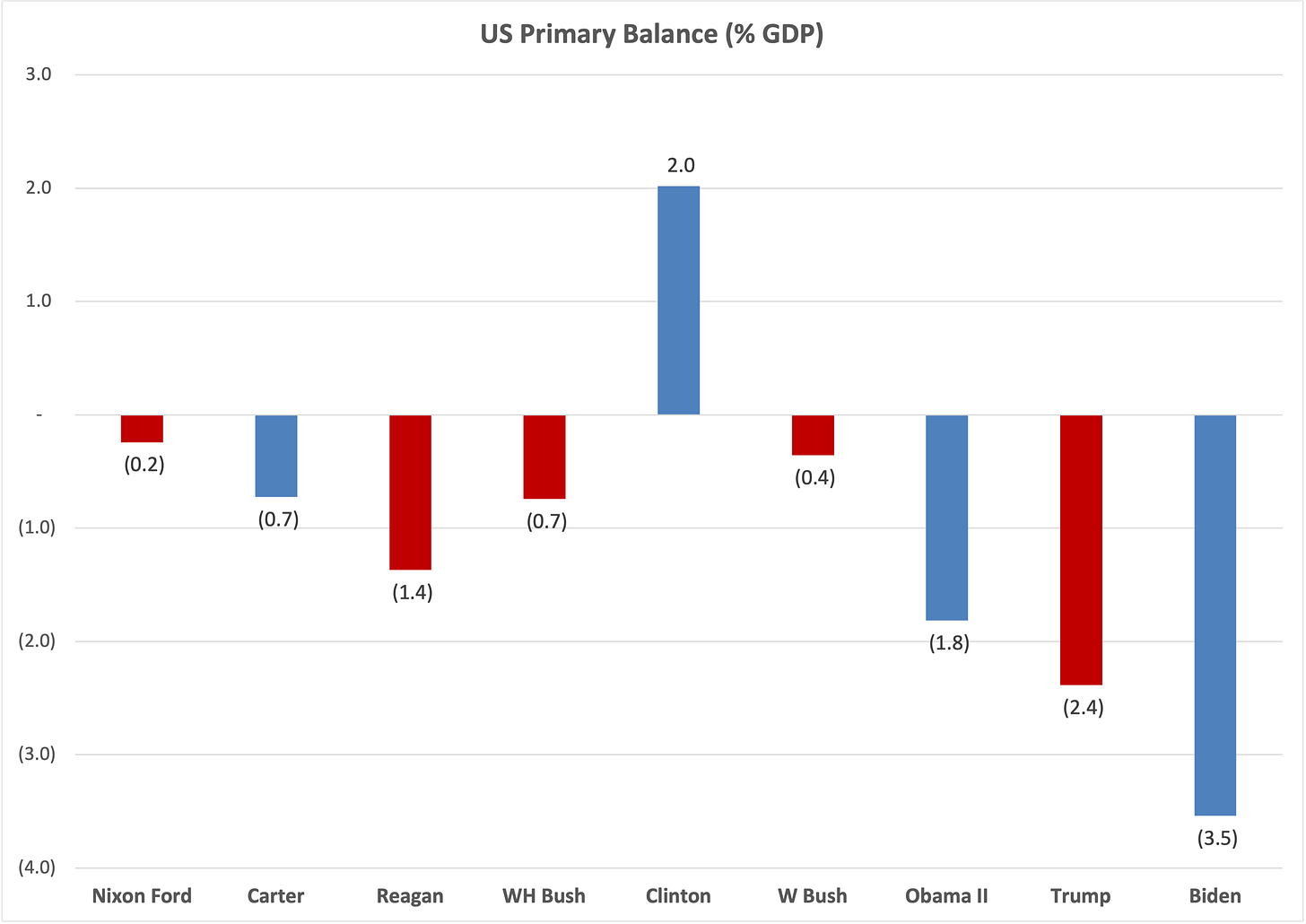

I mentioned interest rates. Most fiscal economists will tell you that a better measure of a government’s fiscal stance is the primary balance, which excludes interest payments on the debt, since those are outside your immediate control. Here is the chart of average primary balances.

Source: Congressional Budget Office; JustThink calculations. Excludes 2009-12 (GFC), 2020, and 2021 (Covid).

Clinton stands out even more. Obama, who as I said benefited from extremely low interest rates, now looks a lot worse compared to Bush — under Obama’s second term the primary deficit was on average almost 5x that of his predecessor. I was secretly hoping that this metric would put the Republicans ahead. It does not. The average primary deficit was 1.0% under Republicans and… 1.0% under Democrats — once again the same to the first digital point.

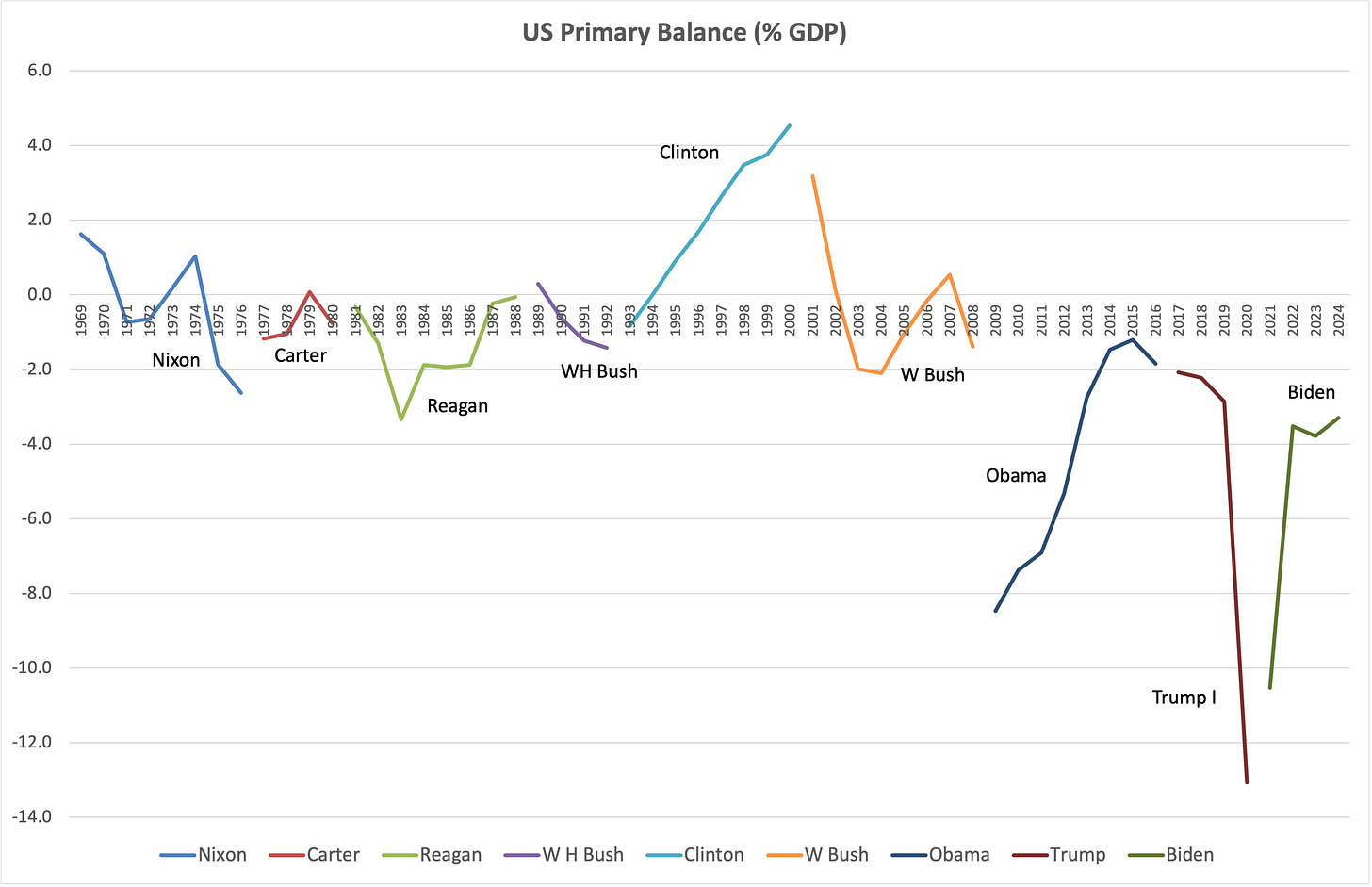

The trends look much the same as for the overall balance:

Source: Congressional Budget Office

I want to spend a few words in defense of Reagan. Under his watch, the deficit widened by 3pp during 1982-83. Of this, 1pp was the rise in defense spending that proved instrumental in winning the Cold War. Interest spending rose by over 1pp during his tenure, courtesy of the fight against high inflation (remember Paul Volcker?) which also caused a deep recession in 1982. And then of course there were the tax cuts, which helped revive economic growth. But Reagan did reduce the deficit over the last five years of his tenure, and in his last two years the primary balance was close to zero, significantly stronger than what he inherited from Carter (-0.8%). So if the benchmark is a multi-year fiscal consolidation that left the government accounts in a stronger shape than they were found, I will submit to you that Reagan also fits the bill.

It’s your money, remember?

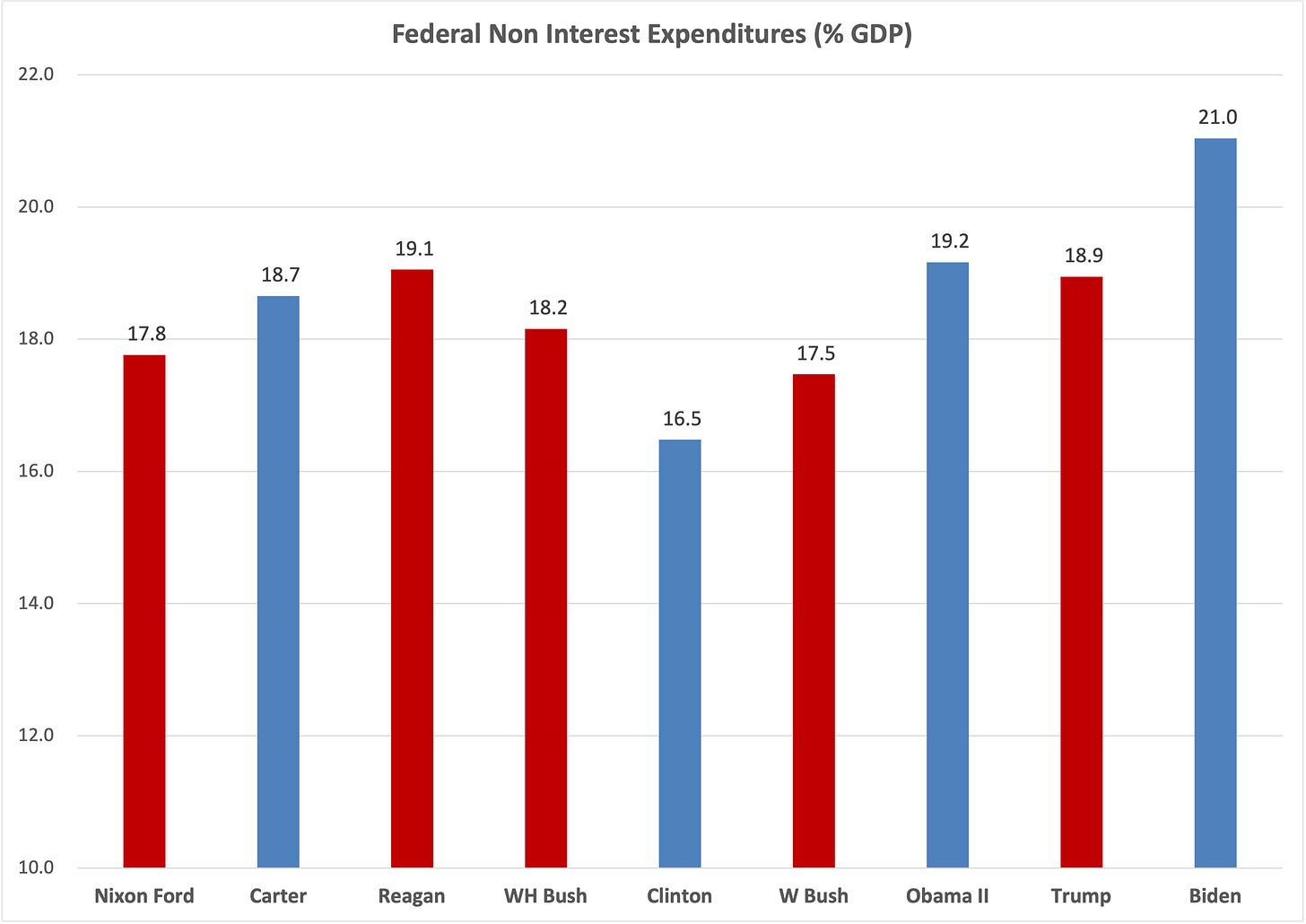

non-interest expenditures today are a full 5% of GDP higher than they were when Clinton left office — an over 30% increase.

And finally, expenditures. Non-interest expenditures, to be precise, because you can’t control your interest payments — not directly, at least. Government expenditures matter because we always need to pay for them: with today’s taxes, tomorrow’s taxes, or tomorrow’s inflation — it’s our money they’re spending.

Source: Congressional Budget Office; JustThink calculations. Excludes 2009-12 (GFC), 2020, and 2021 (Covid).

Here, Democrats look like the bigger spenders to me. Not Clinton — once again, he’s the undisputed hero. If anyone really wants to talk about a third term, Clinton has my vote.

But otherwise: under Carter, expenditures rose by 1pp over the previous administration. They rose a further 0.4pp under Reagan, but that’s less than the Cold War defense boost. W Bush raised them 1pp from Clinton’s low point, but then Obama’s second term raised them by nearly another 2pp. Trump I reduced them marginally, and then Biden jacked them up another 2pp.

Non-interest spending averaged 18.3% of GDP under Republicans, and 18.8% under Democrats — a marginal victory for the red team on this metric. Marginal.

Bi-partisan recklessness

Not that any of this matters. Not anymore.

The deterioration in fiscal discipline that we’ve seen since the GFC is far more concerning — and that’s very much a bi-partisan phenomenon.

The deterioration has been driven by a substantial expenditure increase: non-interest expenditures today are a full 5% of GDP higher than they were when Clinton left office — an over 30% increase. In his last year, Clinton ran a 2.3% of GDP budget surplus; last year we had a 6.4% of GDP deficit — a nearly 9% of GDP deterioration.

We complain about our governments, but we want them to do more and more. We spend our days chasing cheap thrills on social media, and then are shocked that our President makes policy one outrageous tweet at a time.

And as Luca Silipo pointed out in last week’s comments, this is just a symptom of a bigger problem: escalating government intrusiveness in our economies, justified with a succession of presumed existential threats. The GFC, Covid, climate change, and now the AI race. Every time, the stakes are portrayed as being so high as to justify any magnitude and manner of government intervention with no room for public debate.

Trump looks no different. He promises deregulation but favors an interventionist government with his own brand of industrial policy. He shows no desire to bring the deficit under control, and by the time he leaves office the Democrats might well be able to claim the title of ‘more fiscally responsible party.’ Unless we get an economic growth miracle.

Democrats can rightfully boast they had Bill Clinton, the Lionel Messi of fiscal rectitude. Republicans can be proud of Ronald Reagan, the Michael Jordan of free markets. But those days are gone. And as Larry noted, the responsibility ultimately lies with us, the voters. We complain about our governments, but we want them to do more and more. We spend our days chasing cheap thrills on social media, and then are shocked that our President makes policy one outrageous tweet at a time.

It’s not looking good. Anybody else for Bill Clinton 2028?

I agree with Larry and you that when looking at the deficit, there is a lot of bipartisan blame to go around, with the final culprit being the voter...

Still, I think that team elephant, on balance, has done us and our children better than team donkey.

I make 3 assumptions: 1. we have passed the point where US fiscal policy has become unsustainable and will require substantial consolidation; 2. after a certain point (which we have also well passed), a larger government becomes a drag on the economy; and 3rd, the size of government is best measured by expenditure and not the tax take.

Of course, all 3 assumptions are debatable, but I feel quite comfortable making and debating them.

Once we finally have to cut the deficit, the political economy will most likely require a 50-50 mix of spending cuts and tax hikes (with inflation always being an option to cut (the GDP share of) spending, of course).

Team Tusk, having stood in the way of even further baseline spending increases, has thereby likely enabled the US to consolidate without ever reaching even present levels of wealth- and growth-destroying European taxation.

I admit that is little reason to cheer, but at least one slight positive.

You said: ‘The data do show, however, a definite turn towards fiscal recklessness over the past twelve years, and it’s bipartisan’. I say: ‘it’s global’. We need to find another term for debt because the old one implies something Is going to be given back. When the best case scenario is that principal is being repaid with new debt then it’s not debt, it’s something else (help me find the right characterization here)