Making Things vs. Making Things Up

AI, learning, and jobs.

My previous article, on The Manufacturing Fetish, generated a lively debate both on and off-line. Probably because the underlying question is a fundamental one: how is the distribution of jobs and economic opportunities evolving? What jobs will we do? What jobs should we want to do?

Here I want to raise two closely related aspects: education and Artificial Intelligence.

Mind the gap

In my discussion on the importance of manufacturing, I left out a fundamental issue: skills.

Most manufacturing leaders I speak to have long been flagging an emerging skills gap: as older generations of skilled workers approach retirement, there is only a very narrow pipeline of qualified workers ready and willing to take their place. In the US, there are two root causes for this: (1) a very underdeveloped system of vocational training and apprenticeships; and (2) a lingering stigma that causes manufacturing to be regarded as an undesirable occupation.

My former IMF colleague Albert Jaeger noted that behind the desire to bring back manufacturing to the US lies a nostalgia for the manufacturing-based economy of the 1950s and 1960s, associated with high and rising living standards for the middle class. Ironically, though, younger generations have no desire to walk that path. They regard manufacturing jobs as dirty, heavy and dangerous, unaware of how technology has transformed the workplace into a much cleaner, high-tech and rewarding environment.

If we want to bring manufacturing back, this will need to be fixed.

A broader and harder challenge is how to fuel stronger productivity growth across a wider range of sectors. We want faster growth in labor productivity, because that’s what generates stronger wage growth.

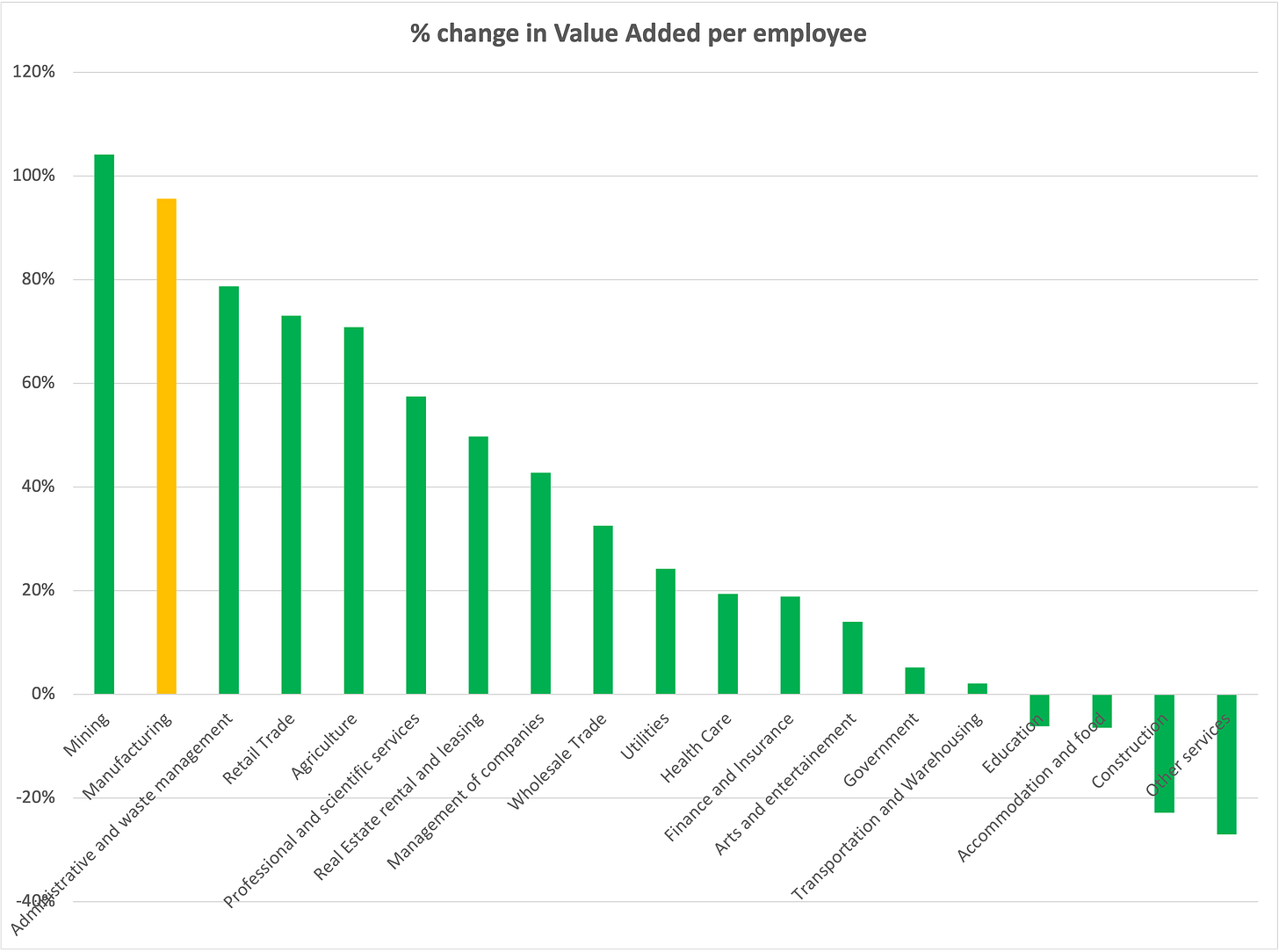

A traditional, sure-fire way to raise labor productivity is to raise the capital/labor ratio. In other words, substitute labor with capital. It works, but doesn’t help much if our goal is to raise living standards for the majority of the population. The most dramatic examples of capital/labor substitution are in agriculture and mining. As I showed in a chart, reproduced below, mining enjoyed the strongest rise in real value added per employee since 2000; agriculture was not far behind.

But the two sectors combined account for less than 2% of total employment.

A better way is to increase the level of skills across the population, so that more people can perform more valuable tasks and be compensated accordingly. This is why a stronger education system has been a key lever for all countries that have risen to advanced economy status.

But the crucial question today is, what skills? What abilities should our education system foster?

Learning, exit stage left

We traditionally measure the quality of education by: (1) the share of students that complete secondary and tertiary education; and (2) their level of knowledge as measured by standardized tests.

These tests have been sounding alarm bells. The latest OECD PISA assessment, released in late 2023, recorded an unprecedented sharp fall in scores across math, science and literacy — equivalent to one year of education lost. One quarter of OECD students struggle to complete basic tasks like using simple math algorithms or understand very simple text.

Enter GenAI. A New York Times Magazine article warns that massive numbers of students are using AI to cheat their way through college assignments, and will likely graduate with very little knowledge of their fields of interest, or anything else, really. This excellent post by Gary Marcus discusses the extent of the problem. Teachers are increasingly frustrated.

What I find most striking is that, for all the talk of hallucinations, way too many students think ChatGPT and its ilk are 100% reliable. This matches my personal experience in casual conversations. Too many of us seem to believe that hallucinations are something that only happens to other people. To refresh your mind on how ludicrously bad these hallucinations can be, take a look at this other post. And then remember that the most dangerous hallucinations are much less noticeable, but no less numerous. Learning, exit stage left.

Another twist to GenAI’s dismantling of education materializes in the form of AI-avatars of historical figures that can interact with students, parroting pathetic platitudes in modern-day slang. Why study the Civil War when you can have a friendly banter with Lincoln over a Diet Coke?

AI can be a force for good in education. The utopian vision of The Diamond Age, where AI becomes a personalized learning companion that stimulates you and helps you learn and grow, will eventually materialize. Hopefully, when it does, our brains will not have already atrophied beyond repair.

Too many of us seem to believe that hallucinations are something that only happens to other people.

And the future of jobs is…

Now comes the really hard part: what skills should we foster? It depends a lot on how you think technology is going to evolve, and the hype around GenAI opens scope for some rather extreme assumptions.

In a recent article on @the free press, economist Tyler Cowen and Anthropic’s (of GenAI engine Claude fame) Avital Balwit argue with strong conviction that,

As AI systems increasingly match or exceed our cognitive abilities, we’re witnessing the twilight of human intellectual supremacy—a position we’ve held unchallenged for our entire existence. This transformation won’t arrive in some distant future; it’s unfolding now, reshaping not just our economy but our very understanding of what it means to be human beings.

Wow. In other words, AI is going to become a lot more intelligent than all of us, like, tomorrow. And this from people who certainly do not underestimate human intelligence — at least their own. With the modesty and understatement characteristic of the industry, Balwit begins with, “I was Claude pre-Claude.”

I find it hard to square these claims with the incurable hallucinations of what is essentially a powerful word predictor without either a model of the world or the capability for generalization and abstract reasoning, but let’s set that aside for the moment.

Cowen and Balwit’s first, worried conclusion is that most of us will be utterly demoralized by the presence of a more intelligent entity. This to me suggests they do not spend enough time on social media. But let’s set that aside as well.

When it comes to the future of work, they predict that blue collar workers will become more valuable, and white collar workers less so, except for those who “use AI heavily to generate projects or guide them in their work.” That makes sense, if you buy the premise. If machines surpass us all in all cognitive tasks, it’s hard to imagine that any of us will be gainfully employed in any cognitive occupation. In the (very near) future they envision, our job opportunities will be circumscribed to being therapists, entertainers, and, I quote because I am not making this up, “greeters, charmers, and flatterers.” Unless you’re a blue collar worker with un-replaceable manual skills, given that robots seem to be lagging behind AI.

I don’t buy their story. I will counter it with my customary “show me the money” argument, or rather “show me the results,” since AI companies have plenty of money to show. What transformational, life-changing innovation has GenAI delivered so far, outside of…well…entertainment?

But you don’t need to buy their extreme vision. Even more cool-headed assumptions on the pace of improvement in AI can underpin a very solid case for reassessing the value of jobs that have to do with making things, rather than making things up.

So, about those manufacturing jobs…

Dear Marco, apologies for the very long comment,

This weekend I listened to your post with my 18-year-old son, and I wanted to share a challenge to your article. I feel your piece views the innovation of AI through a pre-AI lens. I agree—the line is extremely thin and blurry—but can we start shifting our perspective, focusing on how we should adapt to the future rather than lamenting how the future is disrupting the present?

I challenge anyone who believes we can opt out of the AI revolution. Why should we avoid it or renounce its benefits? Yes, AI is a major shock to our cognitive uniqueness and can be dangerous. Many disruptive innovations throughout history have threatened the status quo: the early bushman had better spatial cognitive skills than us, the industrial revolution eliminated jobs in manual textile spinning and weaving; automobiles replaced the need for urban stables and blacksmiths; computers and the internet phased out manual bookkeeping and typewriters. Now, AI is already replacing call center operators, paralegals, and basic software coding. It was never a zero-sum game. Yet we adapted—losing some things, gaining others—and called it progress.

The current skills gap lies in knowing how to use AI to enhance performance, rather than improving obsolete skills that are bound to be replaced.

A positive approach would focus on two main priorities:

1. Educational AI – teaching how to use AI as an enhancement tool, not as a substitute for our thinking.

It should become a core subject: learning how to drive AI instead of being driven by it. Most current articles depict a doom-and-gloom future, which only widens the fear gap and fuels a vicious cycle.

We should teach students how AI can take over tasks where critical reasoning isn't essential, freeing the brain to focus on higher-level thinking. For instance, in writing a lab report, don’t let AI generate the results outright (or generate an income map, as in Gary Marcus’s article). Instead, have students set up the principles and parameters for the experiment manually (starting with Boolean logic: AND, OR, IF), collect test data, and then use AI algorhytm to detect patterns—leaving interpretation and conclusions to human reasoning. In Business delegate all Standard Operation Processes (SOP) to AI interaction freeing up employees tasks from low impact ones. This way, queries are framed within a controlled environment based on word documents instructions translated into code by the AI and allowing it to thrive without overreaching. The common misuse of AI assumes it will replicate human logic or common sense in a vast sea of data—this is a probabilistic impossibility(several articles ref.1-4). It requires an understanding of how AI operates, the principles of algorithmic flowcharts, and the overarching logic of human reasoning.

Another clear example is the criticism of driver assistance systems or autopilot. When things go wrong, autopilot gets the blame. But we should instead examine our own role. Autopilot is just a tool—we are the ones using it. Imagine training aircraft pilots without ever teaching them how to operate the autopilot, leaving it up to them to figure out. Without proper education for operators, we will continue to see accidents increase rather than achieving the safety levels of the aviation industry. The choice between a vicious or virtuous cycle is ours.

2. Pragmatic AI – We should honestly assess which current human activities underutilize our cognitive potential. Using the brain for repetitive or supervisory tasks is a waste of mental power. We need to move past nostalgic ideals, like having a human sell movie tickets or scan barcodes all day at a supermarket.

We must be honest about the daily tasks that involve little to no critical thinking. I'm sure everyone has some of these and finds them frustrating. Imagine, if instantly all these demotivating tasks are handled by AI exactly as you’d like, freeing you to focus on what you love and what motivates you.

We must accept that some human activities can and should be done by AI-powered machines in exchange for more time spent on tasks that truly benefit from our cognitive abilities. If the human brain capacity is roughly equal across individuals, then using the same brain for delicate surgery and for clipping museum tickets is a monumental waste of potential.

The distinction between blue-collar and white-collar jobs is becoming less relevant. AI, when seen as an enhancement tool, cuts across all categories—every job has tasks that are too basic for our cognitive capacity. Our thinking should shift from "What job will AI replace?" to "Which simple or low-value tasks should AI be doing?"

The value added to each job could even rise, making work simpler and more efficient overall.(analysis on increased efficiency with AI ref.5-9)

However, your analysis provides extreme good insights regarding the short term impact on labor force and the future impact of the development of AI into AGI, hence we should be worried to understand better AI, probably the final question is, if short term losses are worth endure to understand how to cohabitate?

"If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change." (Ref. Il Gattopardo)

Great post Marco. I think making manufacturing more attractive for young people is less hard than it seems.

The first obvious thing is that nowadays production hardly happens in the sooty factories described Dickens or in those hyper-dehumanizing conditions described by Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times. I recently collaborated with Autodesk and visited many of their fabrication labs where human creativity is unleashed as machines take away the negative mental space of repetitive work from them. It was exciting and immediately triggered into me an instinct to create and make something.

I think that as you reflect on what can be done - for example in education - to generate the drive to making things, one solution is to wash away from FabLabs, makerspaces, hackspaces, and repair cafes their not-so-subtle leftist-niche coating and preference for Etsy over large scale commercialization. There are unsuspected pleasures fostered by making things - even more when its done together. Co-creation is ideally super-powered by internet and it already works so well in the production and co-production of software through various platforms. We should create the GitHub of the making.

I strongly recommend to anybody this documentary on the making of a Steinway & Sons piano: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6rAhps4AkT8. If you are in a hurry please skip to 18:20 - the short interview to Eddie Salvadon, a plate fitter. Pause and reflect at his story of the concert he attended at Carnegie Hall some weeks before. Eddie should be invited everywhere to share to young people what making things really is.

Among the several damages done by us economists is the dehumanization of the concept of value added, reduced to a number, a percentage. Value added is transferring part of our soul into something we contribute making - a part of the soul which remains embedded in the object and travels with it across places and times; and that we always recognize as ours. This, Eddie Salvadon should share with the young generations.