Discover more from Just Think, by Marco Annunziata

Photo by Markus Spiske on Unsplash

I still stand with you.

Two months have passed since the barbaric terrorist attacks on Israel of October 7th, and the wave of global antisemitism has intensified — a brazen threatening racism worthy of 1930s Europe. The worst examples of ignorant militant bigotry have been on display on college campuses. Institutions that obsess about microaggressions and safe spaces condone a situation where Jewish students are afraid of leaving their dorm rooms — and the Presidents of MIT, Harvard and Penn were shockingly unapologetic about it when testifying in Congress this week. Substitute any other ethnic minority and you will quickly realize how unthinkable all this is — or should be.

So I reiterate what I wrote in the post pinned to this Substack page: To my Jewish friends, to your families and friends — I stand by those words, I stand with you.

Education scores plummet

The latest OECD PISA report, released this week, reveals a further deterioration of education systems across Western countries, with an unprecedented sharp fall in scores across all subjects: math, science and literacy.

PISA is the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment; it tests students at age 15, the latest point at which most are still enrolled in formal education. Their degree of proficiency at that point correlates with performance in the rest of their education journey — for those who keep studying — and in life (see for example here and here.) The decline in scores sends a worrying signal for the build-up of human capital and future productivity and economic growth. It is especially concerning at a time when we worry about the impact of AI and other technologies on the future of the labor market. And it has broader negative implications for the overall health and stability of our societies.

How bad is it?

It’s bad.

Mean scores across OECD countries dropped by 15 points in math and 10 points in reading since 2018 (the previous assessment), which is 3x bigger than any previous change.

In many countries the decline is equivalent to one year of education lost.

About one quarter of OECD students are currently rated as low performers, which means they struggle to complete basic tasks like using simple math algorithms or understand very simple text. (Which helps explain why even in college many of them ignore or do not understand very basic facts, see at the end).

While the drop from 2018 is especially deep, scores have been falling for the past ten years, so this looks like a deep-seated, structural problem.

Go East, young man

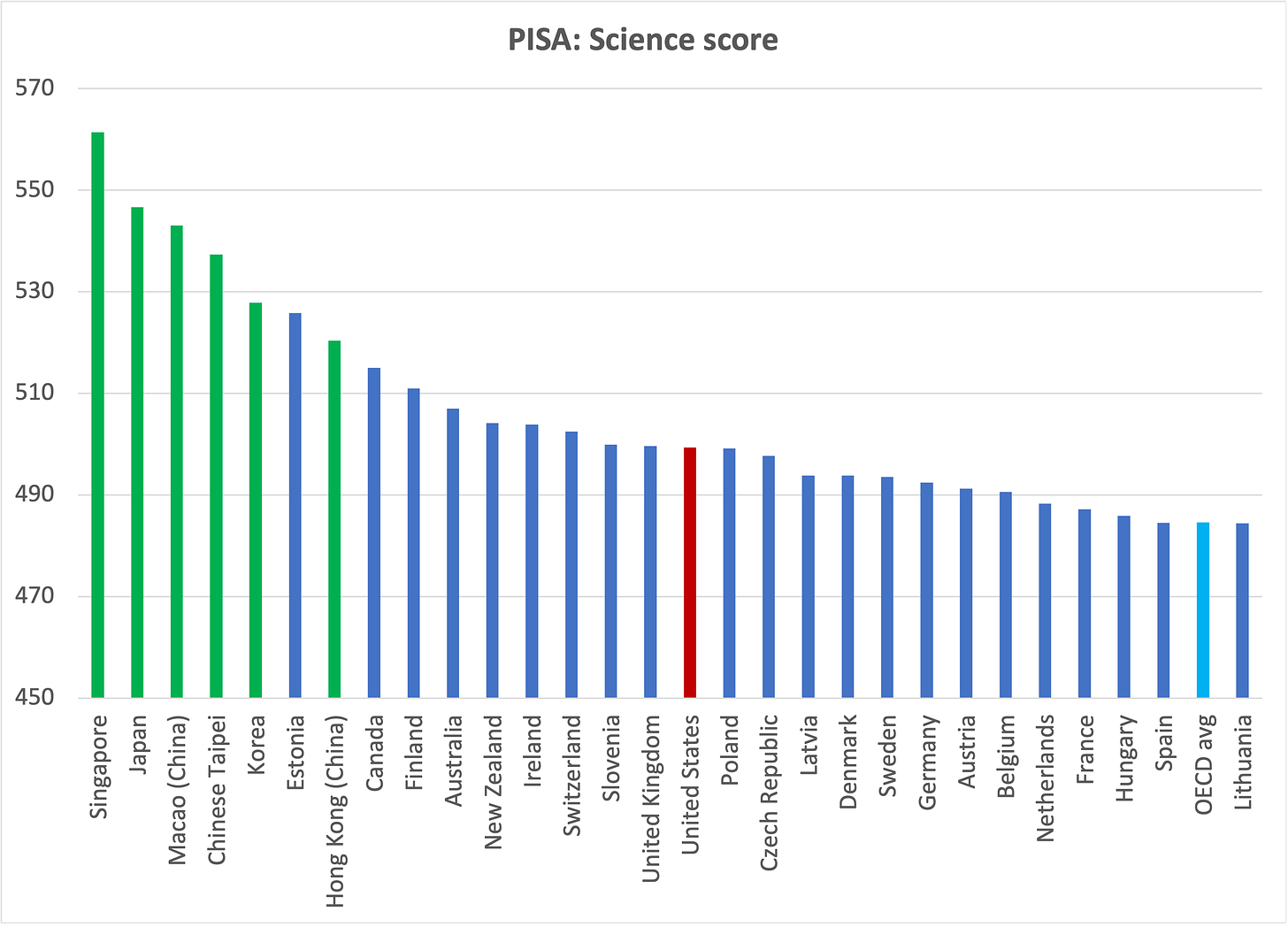

Source: OECD, PISA database

This is overwhelmingly a western problem; Asia continues to value education and maintains excellent performance. Singapore tops the rankings across all subjects, with scores that indicate that its students are 3-5 years ahead of the average OECD student. For kids who have had about ten years of formal education, that is a stunning gap. Five other East Asian education systems outperform everyone else in math and science: Macao, Taipei, Hong Kong, Japan and Korea.

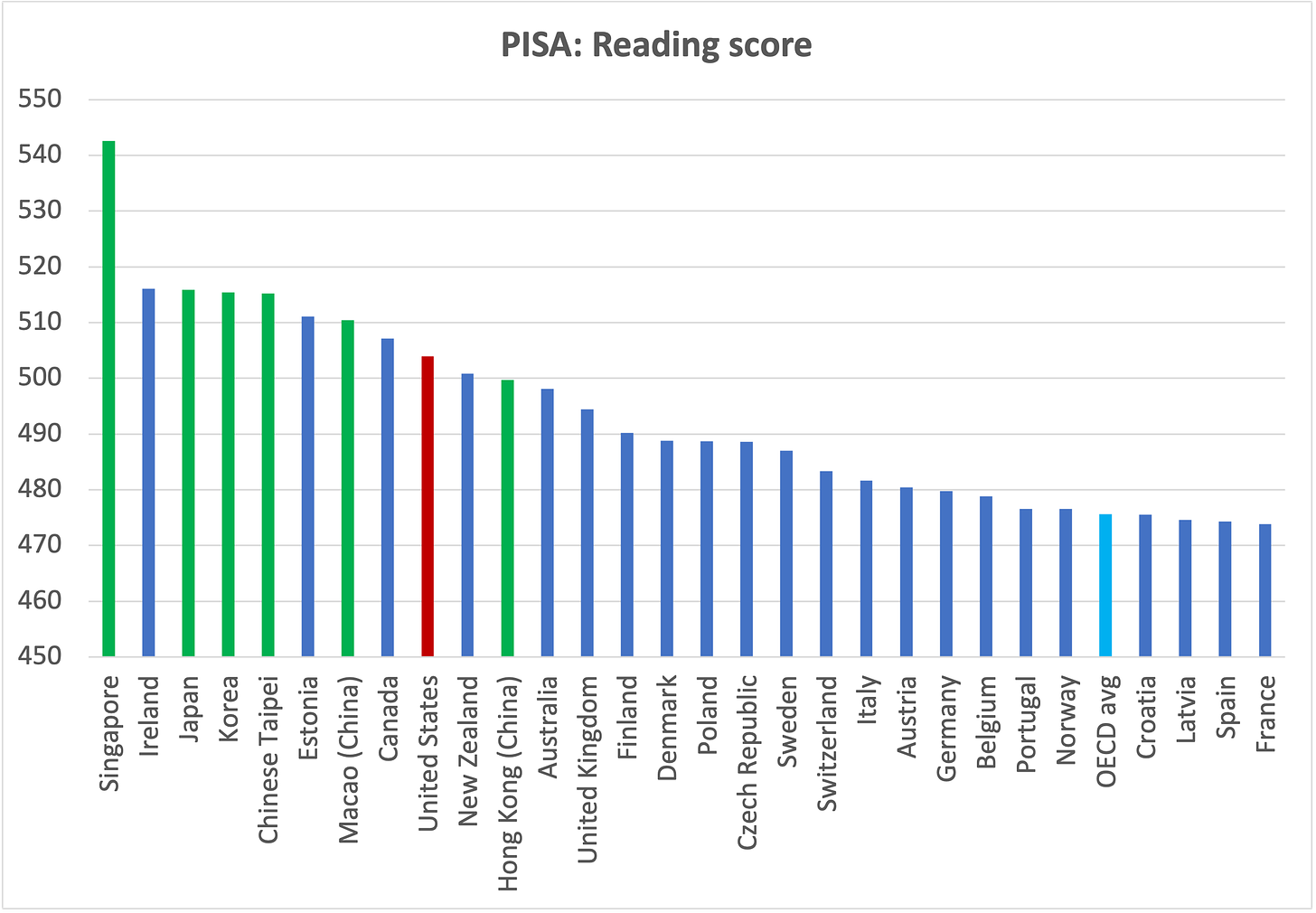

Source: OECD, PISA database

The charts above and below show the top thirty countries in the rankings. I’ve highlighted in green the Asian outperformers, in light blue the OECD average, and in red the U.S.. You will not find a red bar in the math graph — the U.S. ranks at number 35, off the charts, but not in a good way.

Source: OECD, PISA database

This to me suggests two important observations. First, “culture always wins,” as the motto of my Miami gym reminds me. At the top of the charts we find countries whose cultures prize education; their education systems outperform, and immigrants from these countries also tend to outperform within Western schools. Second, this supports a “rising Asia” economic outlook. These days it’s fashionable to highlight China’s failings and to excoriate India (not included in the PISA study); by all means keep criticizing if it makes you feel better, but their emphasis on education excellence will give Asian economies a leg up.

Singapore tops the rankings across all subjects, with scores that indicate that its students are 3-5 years ahead of the average OECD student.

Blame the bug?

The obvious question is whether this sharp deterioration is all due to the massive disruption caused by the Covid pandemic, when countries shut down schools and forced their education systems into a rushed remote learning experiment. Here the study offers mixed signals:

The PISA data show no clear difference between countries that suffered long-lasting school closures (like Ireland) and countries with much more limited ones (Sweden).

But: the report confirms the adverse impact of school closures on student anxiety, loneliness and depression, which certainly isn’t good for learning.

So while I believe school closures have been a catastrophic and misguided error (especially given the extremely low Covid risk for kids), the PISA report does not bring the supporting evidence I would have expected, and suggests that where effective, remote learning has limited the damage.

Technology: a double-edged sword

Technology is both part of the problem and part of the solution, and the PISA report does a good job at spelling out the dichotomy:

The combination of smartphones and social media is addictive and distracting (to say nothing about mental health risks), and the PISA study brings yet more evidence of its destructive impact on learning:

Half of students feel anxious if they don’t have their phone near them.

Two thirds of students get distracted by digital devices (their own or others’) and this has a strong negative correlation with learning outcomes: distraction by digital devices lowers math scores by the equivalent of three-quarters of a year of education.

Students who use digital devices at school for non-learning purposes longer than one hour see their test scores drop precipitously; the longer they spend lost in their phones, the worse the scores.

This is an issue I feel strongly about. Mickey McManus and I have written about the adverse impact of digital technology on human cognition and the possible remedies; Jon Haidt’s

is a great source of data and insights.But technology can also be a force for good in education. It can enable greater personalization and help students learn through computer simulation of real-world experiments. The PISA study confirms that digital devices can help learning, though interestingly the boost to scores all comes from the first hour of use; the positive impact then flatlines, and drops after three hours. So allow digital devices, but in moderation.

Technology can also assist teachers, for example with learning analytics tools that should help them better understand how to keep students engaged. But…

distraction by digital devices lowers math scores by the equivalent of three-quarters of a year of education

Teachers, teachers, teachers…

Perhaps the most damning insight in the report is that teacher support for students has dropped significantly over the past decade, even though class sizes and student/teacher ratios have if anything improved. The problem therefore seems to be not the number of teachers, but their quality, motivation and engagement — and that’s a serious problem.

Until we get to the Diamond Age world where AI can become your personalized tutor (see below), the role of teachers remains paramount. The report suggests that many countries need to figure out new ways to improve teachers performance.

Bankrupt

Education systems across many Western countries are failing — and failing us. We can and should have a deeper discussion on how schools can do a better job at preparing students for a world where technological disruption moves at an accelerating pace. Advances in Artificial Intelligence will likely make some of what is being taught in schools today obsolete or redundant. But to take advantage of new education technologies and the new opportunities that innovation will offer, we still need proficiency in basic math and science, as well as literacy — and we’re doing a worse and worse job at building it.

Schools need to more effectively equip students with the ability to understand texts (no, not the emoji-filled texts on their phones…), to think logically and creatively, to solve problems. And they need to stimulate curiosity.

Failure to do so is especially problematic in societies where academia, the media and government have taken the habit of presenting us with unquestionable truths, shutting down debate and censoring unwelcome opinions (climate, Covid), and routinely demonizing political opponents as “fascists.” Unsurprisingly, university students do not feel they even need to find out the basic facts before strongly supporting a view and shouting slogans they do not understand (the ignorance of protesting students on the basics of the Israel-Palestine issue is shocking.)

Either schools start doing a better job, or we’d better hope AI takes over.

Miscellaneous observations:

Shocking: the proportion of students who reported “not eating at least once a week in the past thirty days due to lack of money to buy food”is 8% on average across the OECD, 13% in the U.S., 11% in the U.K., 19% in Turkey. Enough said.

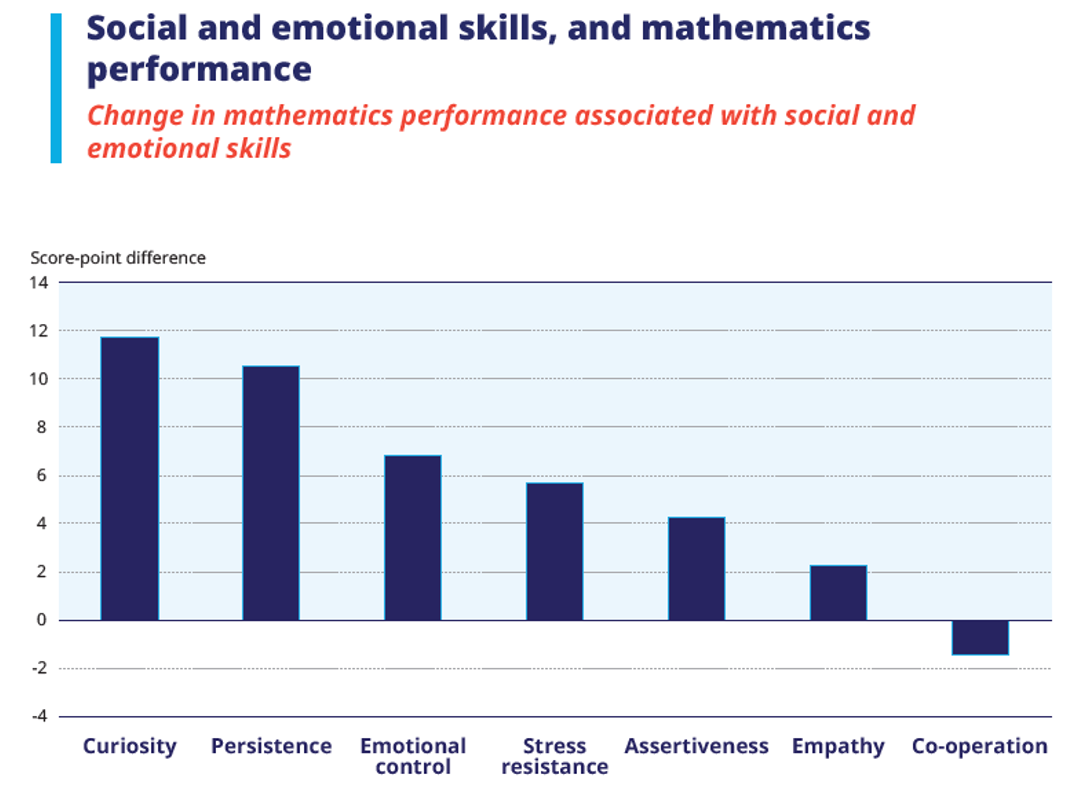

Amusing: in a section on “the power of emotional intelligence,” the report shows the following chart illustrating how different aspects of emotional intelligence correlate with strong performance in math. Perhaps the section should have been titled “the power of curiosity”…and you can see why the report does not dwell on the power of empathy and cooperation:

Source: OECD, 2023 PISA report

Further reading: I would highly recommend Neal Stephenson’s sci-fi novel The Diamond Age for a glimpse at the potential future of AI-powered personalized education; for more on the role of digital technology in disrupting higher education and life-long learning, try this white paper I co-authored with the Pearson team.

Subscribe to Just Think, by Marco Annunziata

Stepping away from groupthink, with a focus on economics and innovation

Can't fault your arguments and it correlates with a lack of rigour that is very evident when dealing with so called trained and supposedly professional people who seem to have little clue and a very narrow outlook except for gazing in to their phones. It also answers the falling productivity issue. Merry Christmas Marco...and peace on Earth as it seemingly spirals inexorably to Armagedon. :=(