3%

A higher inflation environment: The Fed is ok with it, and we should get used to it.

Bending to political pressure, the Fed cut interest rates by 25 basis points this week.

No, wait, let me try again.

The Fed reaffirmed its independence this week, cutting interest rates by 25 basis points.

Observationally equivalent, I guess — but the latter is the true story. The Fed, and Chair Powell in particular, handled well both the unseemly political pressure and the complex economic challenges. This September policy meeting provided important insights on both.

Inconsistency check

I will start with some criticism, though. Compared to June, the Fed now expects:

Stronger Growth: +0.2pp in 2025 and 2026, +0.1 in 2027

Lower Unemployment: -0.1pp in both 2026 and 2027, no change for 2025

Higher Inflation: +0.2pp in 2026, no change for 2025 and 2027

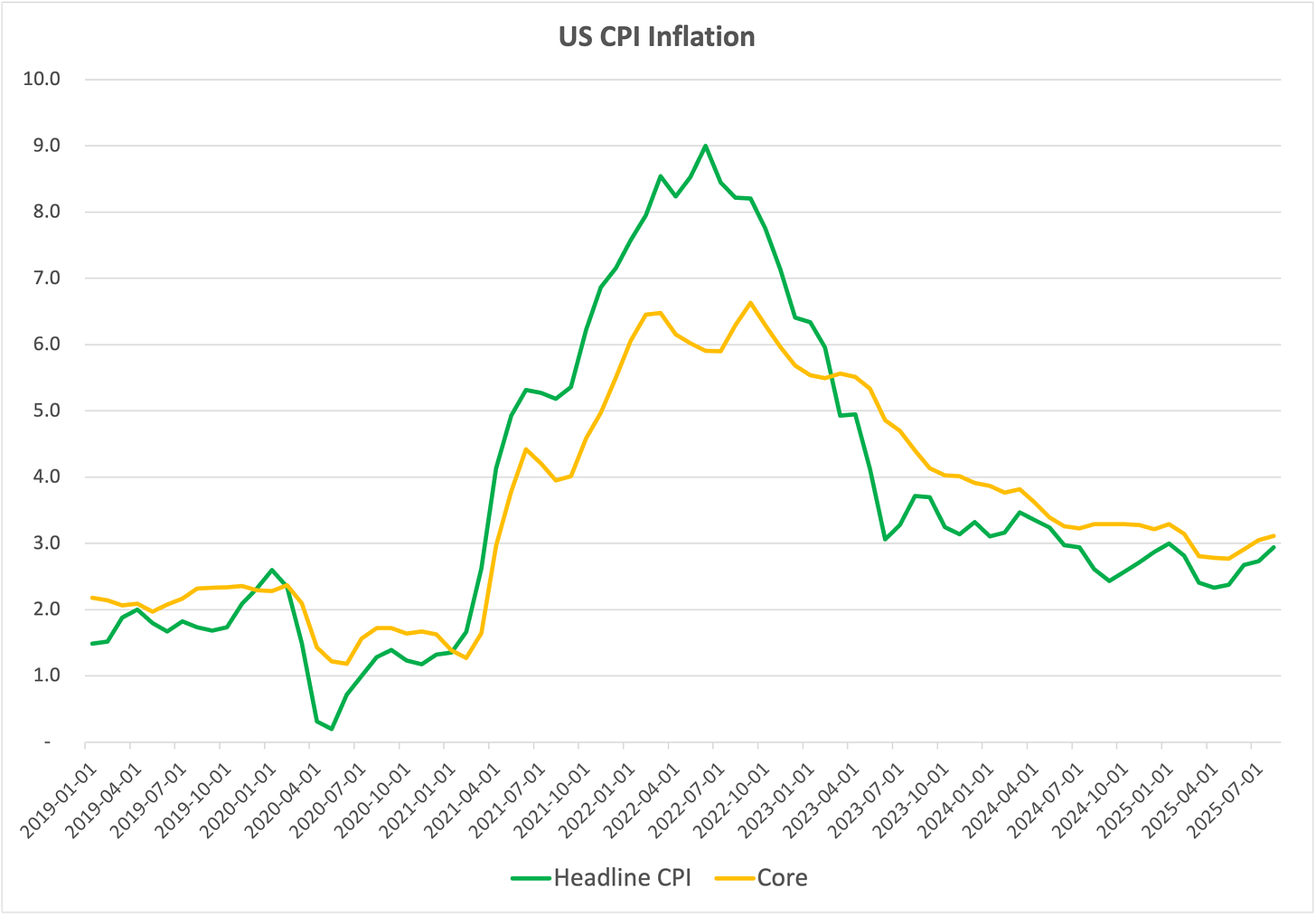

Inflation is running 50% above target, at about 3%, with no progress on disinflation for last two years on headline, one year on core.

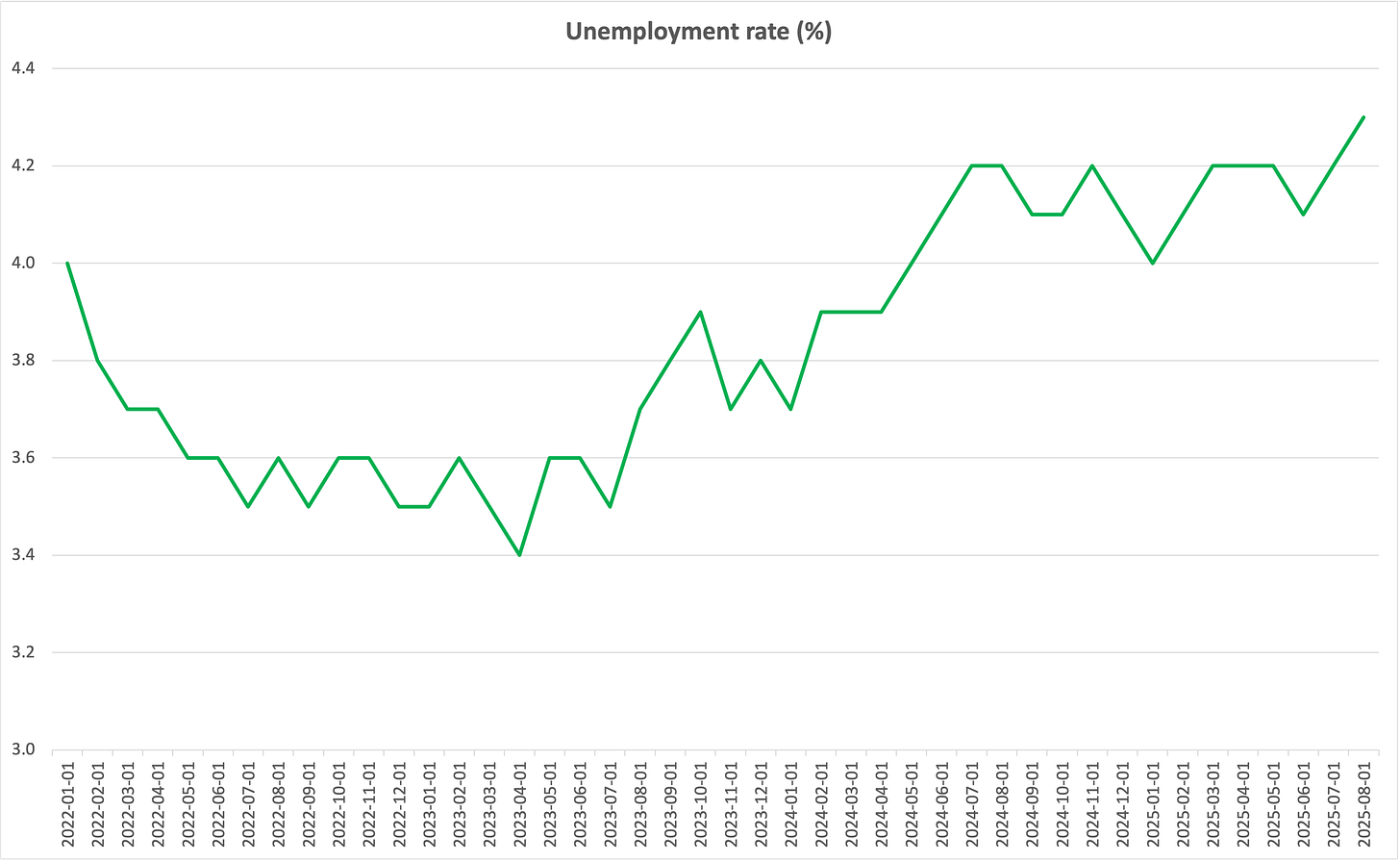

The labor market, by the Fed’s own reckoning, is at or close to full employment: the August unemployment rate was 4.3%, just 0.1pp higher than a year ago, and in line with the Fed’s assessment of equilibrium at 4.0-4.3%.

If the labor market is on target, inflation too high, and you expect unemployment to fall and inflation to rise, how do you justify cutting interest rates?

Risk management, of sorts

As a risk management move: the Fed sees risks to employment greater than risks to inflation. Job creation has weakened, and they now feel labor demand is decelerating more than supply, because the unemployment rate has risen. Fair enough, though the rise in unemployment is just one monthly data point so far. On the other side of the mandate, tariffs have boosted some prices, but not the overall price level. The Fed feels more confident any inflation bump would remain temporary, given the weaker labor market. Fair enough, though this might underestimate the resilience of consumption — retail sales were strong in the past couple of months.

The Fed prioritized employment and is willing to take greater risks on inflation. No surprise there, it’s what the Fed always does. Though it’s riskier this time around, given the deep scars left by the recent inflation surge.1

How many divisions does the Pope have?

A recurrent question in recent weeks has been, ‘How many Fed governors does President Trump have?’ Wednesday’s meeting showed this might not matter: Trump now ‘has’ four governors, but he only got one vote. Powell, Waller, Bowman and Miran are all Trump appointees; Miran was the only one who dissented from the majority, voting for a 50bps cut, and reportedly penciled in an absurdly low end-2025 ‘dot’ in the interest rates projections. Nobody else supported him.

Institutions matter: the Fed is still independent. But people also matter: Miran should not be on the FOMC. The fact that he maintained his position in the administration, taking only a leave of absence, is inappropriate. Congress should bear this in mind in future confirmation hearings.

3%

Mark Sobel asked in a recent piece whether the US is moving towards a 3% inflation regime. I would argue we are already there. In some ways, it’s a smart strategy for the Fed: 3% is as good as 2%, as long as inflation remains stable, and for the past two years that has indeed been the case. Why risk higher unemployment just to nudge inflation a bit lower? More than an undeclared target shift, it’s constructive ambiguity. The Fed will be happy to go back to 2% if it can do it painlessly. If.

The open question is how financial markets, businesses and workers will react as they internalize the shift. We might see somewhat more aggressive wage demands and pricing strategies, but in the end wages and prices will be driven by supply and demand in the relevant markets.

One thing that’s for sure, however, is that if inflation settles at 3%, the neutral fed funds rate cannot also be at 3%. That would imply a real policy interest rate of zero, which makes no sense in a healthy economy growing at a 2% potential pace.

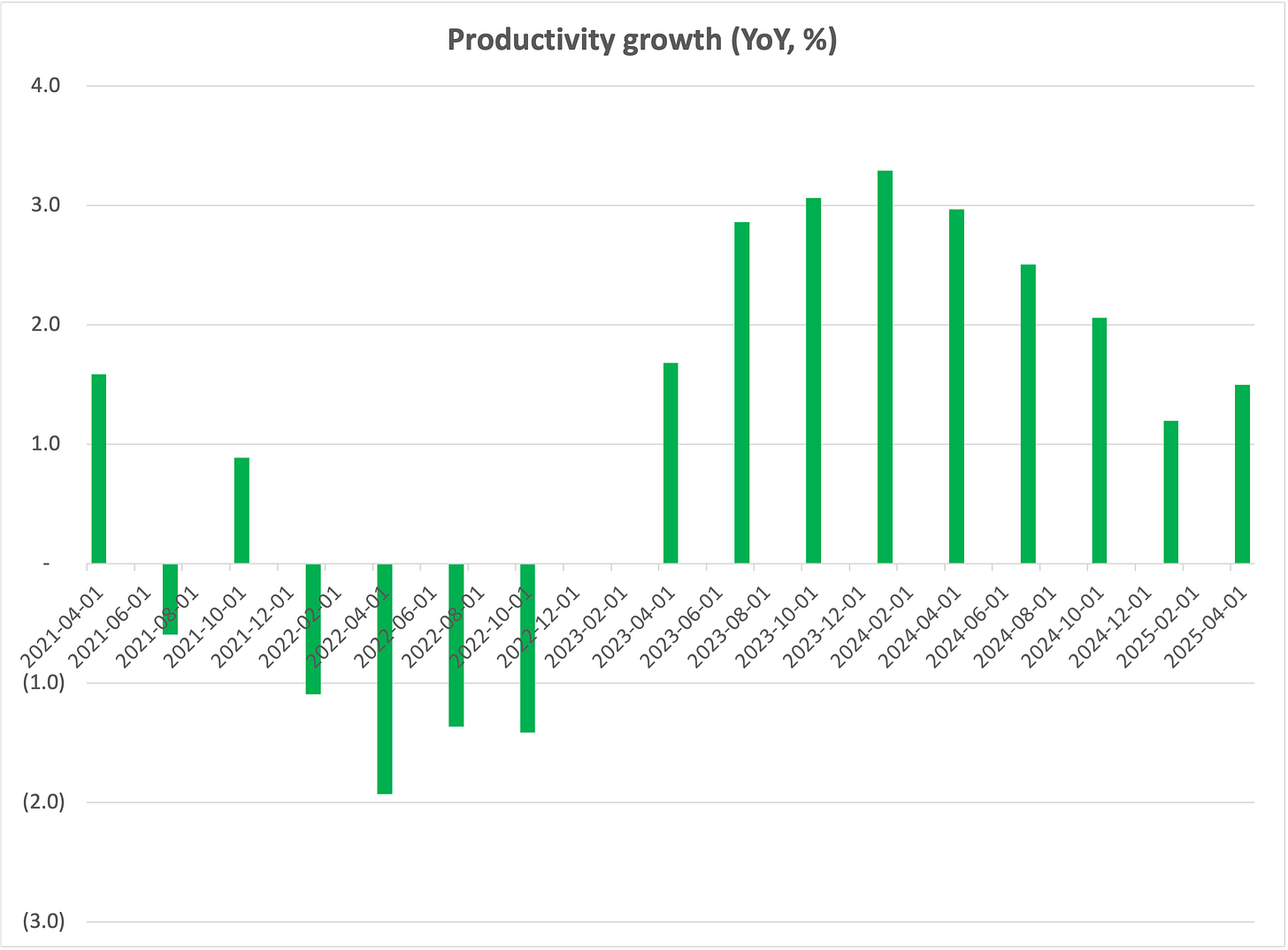

US productivity growth averaged 2.4% over the past eight quarters, signaling that innovation might be starting to deliver some efficiency gains. With this kind of productivity growth, a 3% inflation rate would imply policy rates of at least 5%, and 10-year bond yields higher by a reasonable term and risk premium.

Yet the Fed still sees the natural fed funds rate at 3%, and 10-year Treasury yields are at around 4%. I think both the Fed and financial investors have some significant repricing to do…

This is also consistent with a more benign interpretation of the Fed’s forecasts: Fed officials expect higher inflation and lower unemployment because they expect to loosen monetary policy. (Those forecasts are not a consensus exercise but the aggregation of individual members’ projections, so you can only go so far in weaving a consistent story behind them.)

I don't think anyone in Turkey or Argentina would call that stability... I take your point about not causing a recession for some number chosen by New Zealand central bankers (I think). It's just that we all need an anchor even if the anchor slips a little from time to time.

Et tu, Marco? Sure, 3% is close to 2%. It's also close to 4%, which is just a step away from 5%...