Insanity Check (Part II)

We need to talk about those financial markets. And we need to raise our standards.

In Insanity Check Part I, I argued that we need a serious reflection on global trade imbalances.

The market reaction to Trump’s tariffs should also give us pause. At the peak of the tariff fear, Trump’s Liberation Day announcements had wiped out over $10 trillion in wealth from global stock markets. That is a staggering figure, and it has been taken as proof that upending the global trade order could cause catastrophic damage to the US and world economy.

The growth risks of a global trade war are undoubtedly severe.

But…

Easy come, easy go

During 2024, the S&P 500 alone “created” over $10 trillion in wealth. Was this justified by phenomenally strong global growth? By an unprecedented, growth-enhancing revamp of the global economic order? It should have been, to mirror the logic of the tariff-related wealth destruction.

When equity markets create paper wealth, we tend not to question the fundamental reasons. Yes, we do occasionally worry about bubbles, but we tell ourselves that the promise of future growth has suddenly improved so much that stock market gains are justified — the AI wave is the latest example. When the paper wealth gets blown in the wind, however, we feel that only some tangible dramatic change in the fundamentals can justify our losses.

Unsafe havens

We now accept — worse, we elect — leaders whose brainpower, knowledge of history, command of the issues, poise and polish are woefully unequal to their responsibilities. Trump is a striking example, but this is not just a Trump issue.

More disturbing has been the sell-off in US Treasuries. Analysts have noted that it might be driven by foreign countries selling US bonds; or by hedge funds unwinding gigantic and highly leveraged positions on “basis trades”. Volatility in the safest of safe assets has once again raised fears that a new financial crisis might be brewing. I don’t think that’s the case, but the very fact that we are posing the question again highlights the problem.

Decades of loose global monetary policies have left us with a financial system awash in liquidity, hooked on leverage, and out of proportion with the real economy. This causes gyrations of boggling magnitude that monopolize the headlines. In the best case, they give us a wildly exaggerated sense of what’s happening in the underlying economy. In the worst case, they can actually drive a genuine economic crisis, as in 2008.

Regulators regularly promise to put in place infallible safeguards, but then, unfailingly, we get a new scare — remember the Silicon Valley Bank fiasco, also centered on US Treasury holdings?

This is an issue that deserves serious thought.

End of an era?

The other notable feature of the market reaction has been the simultaneous sell-off of US equities, US government bonds and the US dollar. The last two were counter-intuitive: tariffs should strengthen the dollar, and US Treasuries normally act a safe haven, attracting greater investment when risk aversion spikes. Instead, the opposite happened. This sell-off trifecta seems to point at a broader loss of confidence in US assets — and in the US overall. Is it true? Maybe. Is it justified? Only in part.

US policymaking looks pretty poor right now. As far as tariffs are concerned, “the execution is execrable” is the best characterization I’ve heard, about fifteen minutes into this Money Talks podcast. (I love alliterations). The fact that the US President can misuse emergency authority on trade policy without anybody batting an eyelash does not speak well of the strength of our institutions.

Meanwhile we’ve seen no concrete progress on either deregulation or tax cuts, the crucial pillars of the administration’s pro-growth agenda. Nor have we seen any concrete progress in reducing the absurdly large fiscal deficit. I remain hopeful during the day, but at night I have nightmares of the US becoming like Europe, with an election choice between pro-immigration economic socialists and anti-immigration economic socialists…

Whether this crisis has inflicted unrecoverable damage to US soft power merits a longer, separate discussion. But there is no doubt that the US today inspires less confidence.

For financial markets, however, the question is, what are the alternatives? Can US Treasuries be displaced as the global safe asset of choice? Maybe, but where are you going to go? You think the market for German bunds is liquid and deep enough? Because remember, Europe has a single currency but not a single government bond market. The same holds for the US dollar: global reserve currencies are made and unmade over decades, not weeks or months, as the above-mentioned podcast reminds us.

To put things in perspective, look at where the US dollar stands against two main global competitors, the euro and the Japanese yen. Here is a chart of the dollar-yen exchange rate over the past ten years. A higher value means a stronger dollar:

Source: St. Louis Fed’s FRED database

The dollar is still a lot stronger than it’s been for most of the last ten years. It is now about 30% stronger than five years ago.

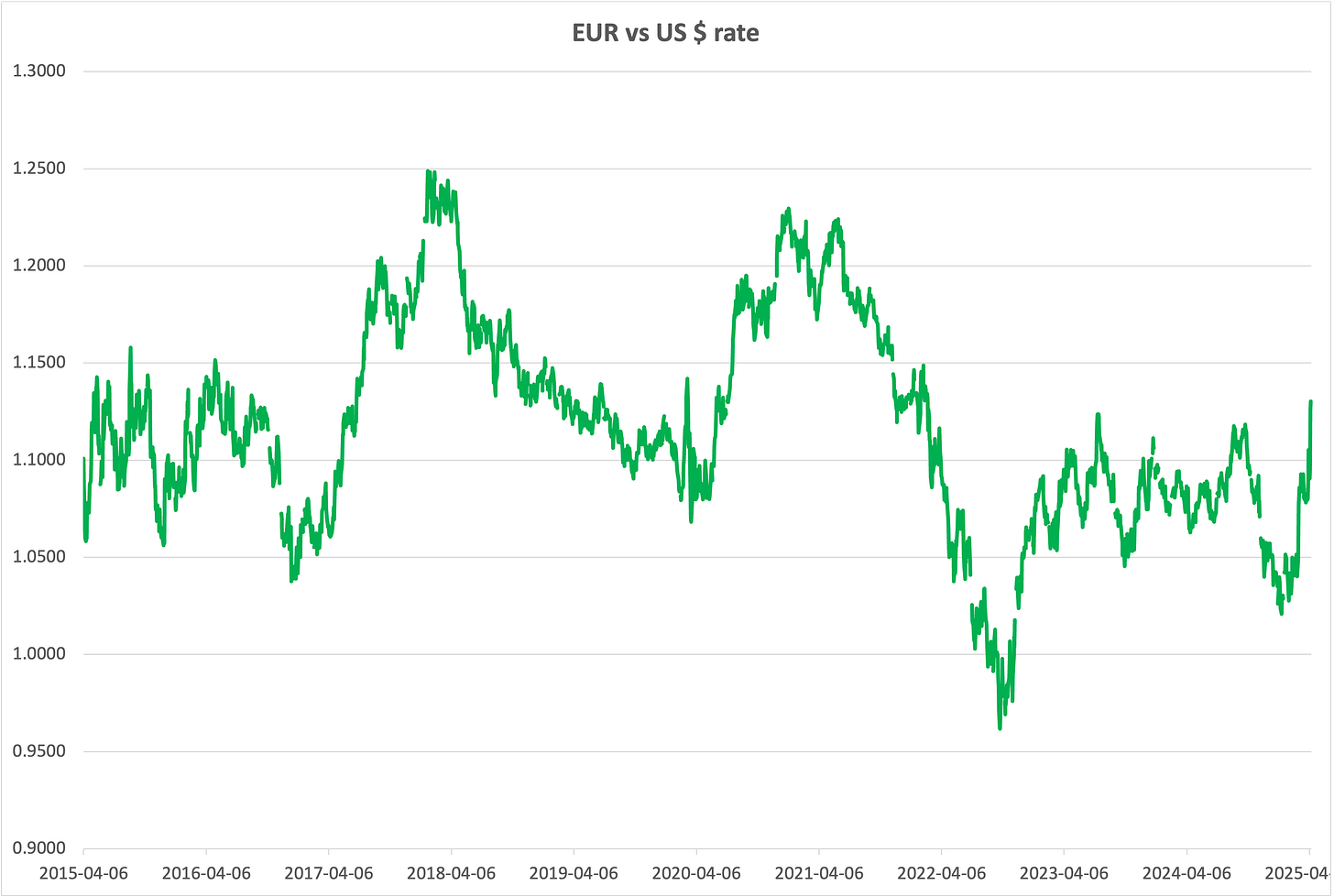

Now the euro — here a higher value means a weaker dollar. Against the euro the dollar is weak, but not the weakest it’s ever been. The dollar is about 8-9% stronger than it was in January 2021 or in February 2018.

Source: St. Louis Fed’s FRED database

This is what floating exchange rates do: they float, on the waves of economic and financial market fluctuations. I understand that many people around the world and some in the US want to believe that the reign of the dollar as global reserve currency has come to an end — but I’m afraid you’ll have to wait a while longer.

Oh how our standards have fallen

I will close with two considerations.

The first is that the most dangerous trend, in my view, is the lowering of standards. We now accept — worse, we elect — leaders whose brainpower, knowledge of history, command of the issues, poise and polish are woefully unequal to their responsibilities. Trump is a striking example, but this is not just a Trump issue.

The second, related point is that sensationalism and social media addiction have hijacked our politics, setting exactly the wrong incentives for our leaders. It makes me laugh to see talking heads on TV blaming Trump for his bombastic behavior — it is tailored exactly to have maximum impact on their talk shows. None of the media ever tries to genuinely inform us and encourage us to (just) think through the issues. They thrive on outrage. Social media, of course, are even worse, and policymaking itself now seems to be guided by social media dynamics. This is particularly true for Trump but again, this is not just a Trump issue.

If we really want to change course, we need to raise our standards. And it has to start with everyone of us.

We need a check on this insanity.

I could not agree more about how the standards have fallen, I always say Trump needs a good and knowledgeable economist 😉

The author seems to want at the same time significant tax cuts and large reduction in the government deficit. I am afraid there is a contradiction. Pls do not respond: ‘cut waste’. Like in other industrial economies the government budget consists increasingly of government transfers. Unlike other Republicans, Trump has never played with the idea of cutting Social Security or Medicare. And this is one of the reasons why he has been elected President. The US has more room than most for increasing taxes or reducing defence spending, but I guess this is off the table. In spite of significantly lower growth potential, the real interest rate on government debt puts Germany in a better position to sustain its debt: this seems to me a pretty damning verdict on US economic policies.