Fiscal Mental Meltdown

We have a serious fiscal problem. We should discuss it seriously.

I have very mixed feelings about Trump being President, and I am reluctant to say anything positive after the raft of family business deals that punctuated his latest Middle East trip. But one important benefit is that we can now talk openly about the fiscal mess we’re in.

This past week has been dominated by fiscal policy: the ‘big beautiful bill’ has passed the House, and Moody’s rating downgrade highlighted the shaky US budget outlook.

Spenders anonymous

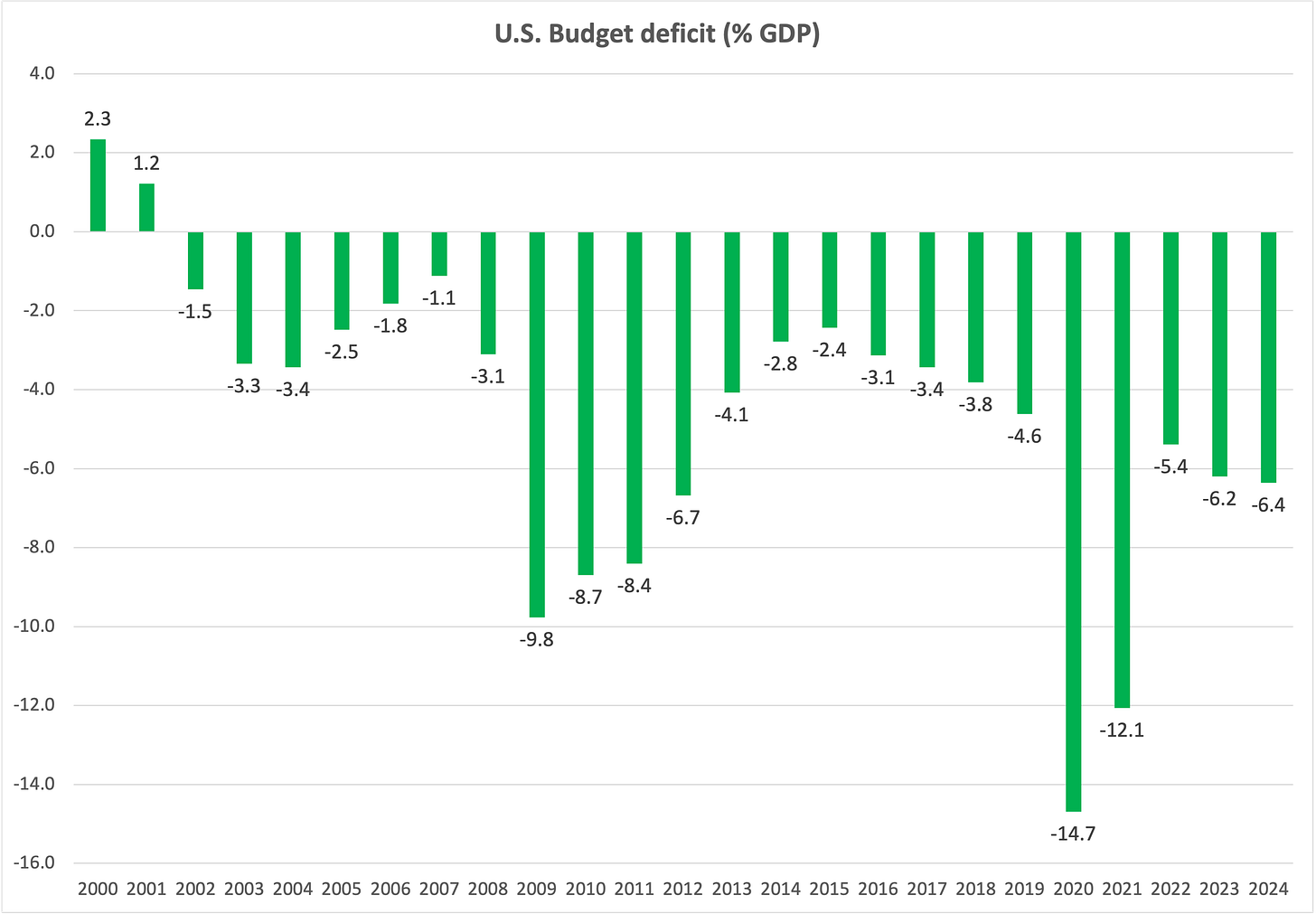

Over the past three years, the US fiscal deficit averaged a substantial 6% of GDP, even after the economy had recovered handsomely from the Covid shutdowns. This fiscal largesse came on top of a shocking cumulative 27% of GDP deficit during 2020-2021. That pandemic stimulus already looked excessive; but pumping an average of $1.5 trillion deficit a year into a strong economy was reckless. To raise concerns, however, was seen as treasonous. Now that Trump’s in charge, criticizing deficits has instead become de rigueur.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

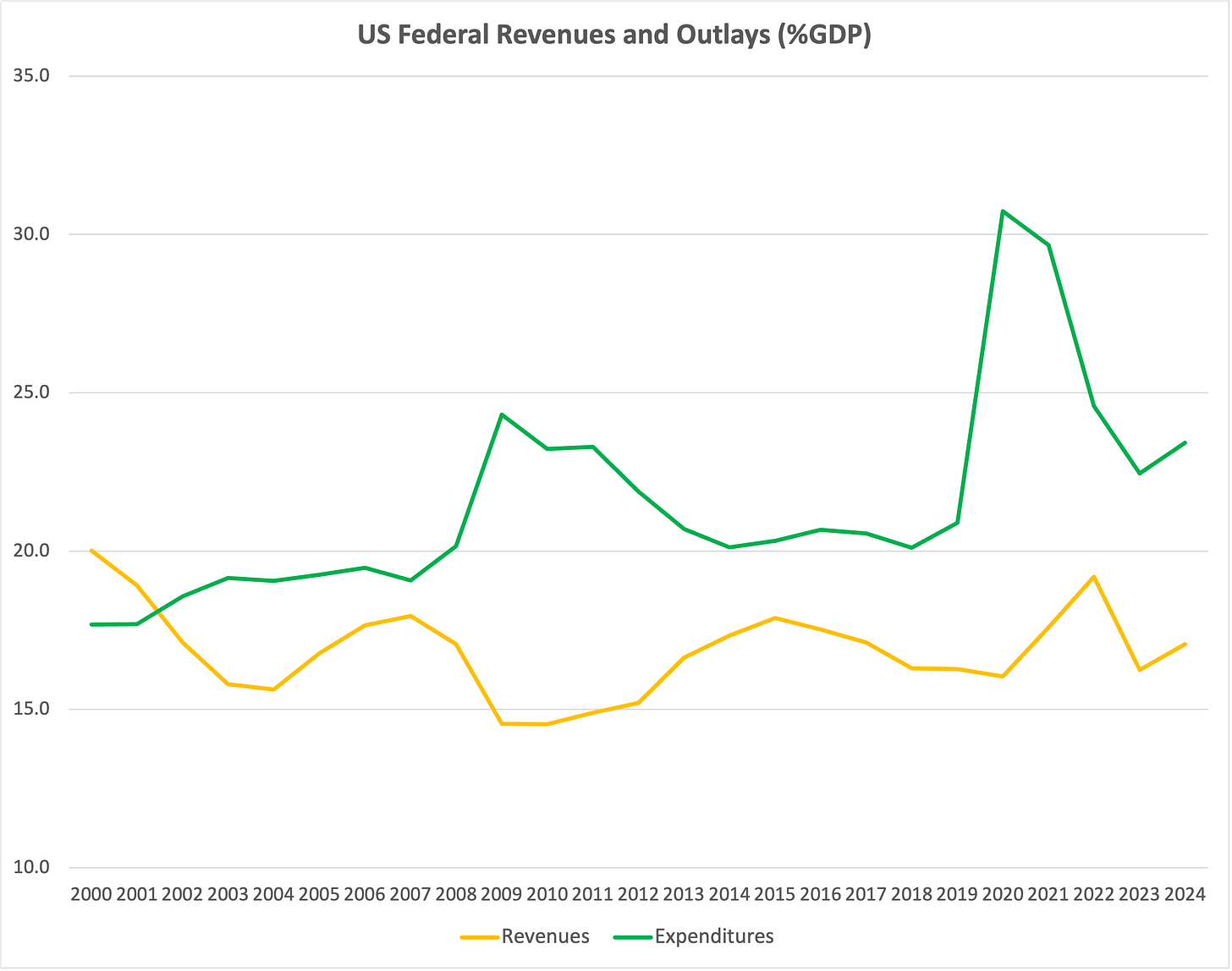

Large deficits have not been driven by tax cuts, but by massive sustained spending increases. Last year, federal revenues were at the same level as in 2017, before the tax cuts kicked in. Expenditures instead have surged and settled on a higher plateau.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

Not the ugliest pig

global fiscal recklessness was cheered on by many of the same people now wringing their hands about US debt.

Moody’s decision marked the definitive loss of AAA status, so there is a temptation to weave it into the narrative of vanishing US leadership, with US government bonds and the dollar doomed to lose their primacy. But there are three problems with this logic.

The first is that Moody’s was just playing catch-up. Standards & Poor’s downgraded the US fourteen years ago, in 2011. Fitch in 2023. Moody’s decision conveyed absolutely no new information.

The second is that it’s not clear why we should be paying any attention to rating agencies. These very same institutions had assigned top ratings to the financially engineered junk that caused the Global Financial Crisis. It’s remarkable that they are still in business, and dispiriting that anyone still listens to them.

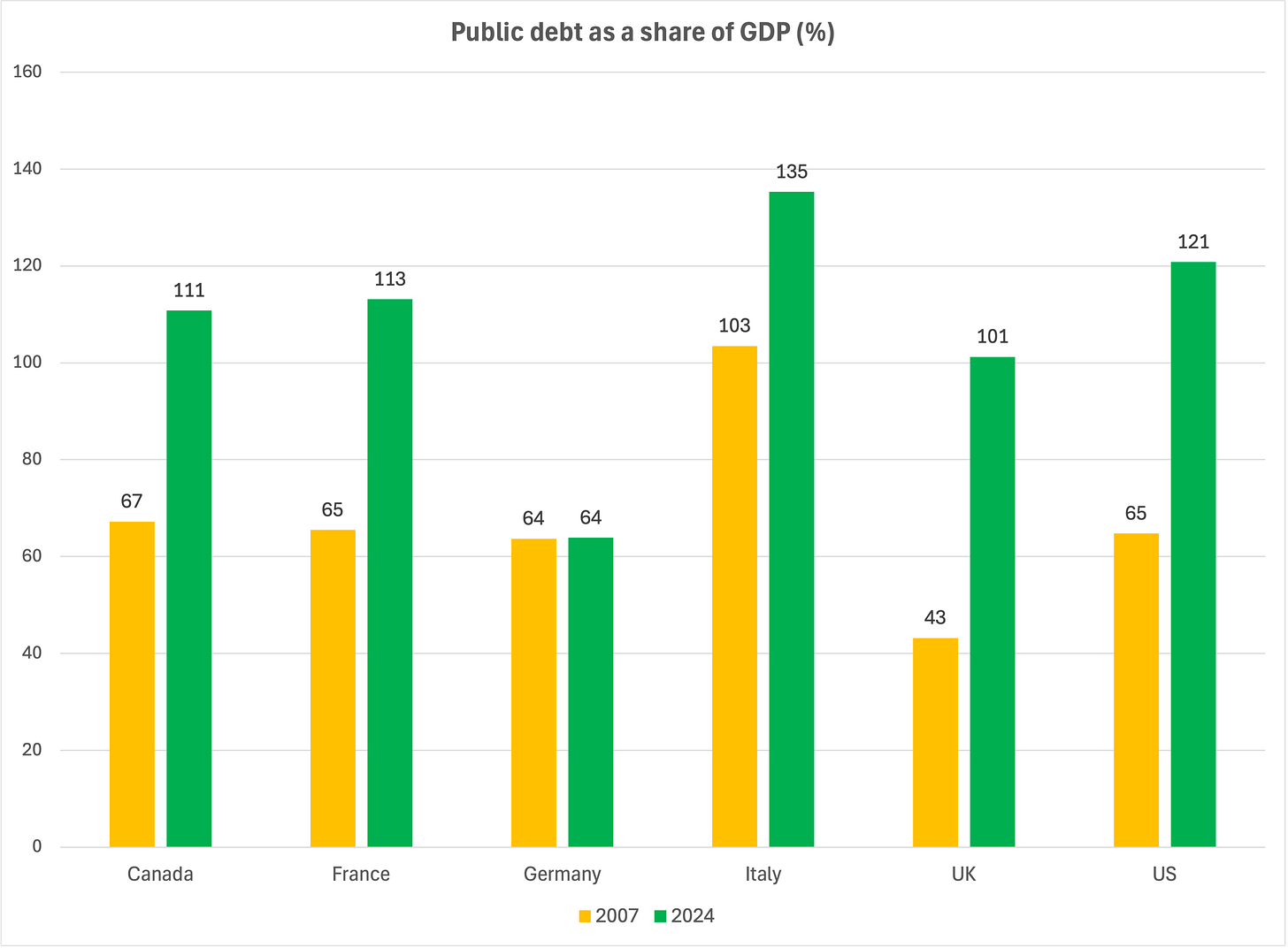

The third is that while the US is an ugly fiscal pig, it is not the ugliest pig on the farm. Over the past twenty years, nearly every single Western government has been on a spending binge, and debt levels have soared across the board, as the chart below shows:

Source: IMF

This global fiscal recklessness was cheered on by many of the same people now wringing their hands about US debt. Previously they insisted that governments should keep borrowing with abandon because interest rates would forever remain near zero. The result is that nearly everyone now has a massive government debt problem. And in this sorry crowd, the US remains the country where robust economic growth has the best chances to help keep the debt ratio under control — though it won’t be enough.

Speaking of which, here is an amusing inconsistency: while loose US fiscal policy is now heavily criticized, Germany’s decision to jettison its long-standing fiscal restraint has met enthusiastic approval. Yes, I know: Germany can afford it, given its low debt ratio; but if you value fiscal prudence you should mourn the capitulation of the last bastion of responsibility.

Arbitrary, twice over

There is one aspect of US fiscal policy which in my view is far worse than in most other countries. It drives me nuts. The impact of a budget bill is measured in terms of how much it will ‘cost’ over a ten-year period compared to a current law baseline. This means estimating the impact of proposed fiscal measures over an arbitrary long horizon against an arbitrary baseline, resulting in arbitrary numbers that convey no useful information. The big beautiful bill is estimated to cost just over $3 trillion over the next decade. What does it actually mean?

The arbitrary time horizon leads to arbitrary deadlines. Example: the new bill would exempt tips from taxation, but only until 2028. Why? I can only assume the phase-out helps reduce the ten-year cost while allowing Trump to claim he kept his promise. That’s a stupid way of making policy.

The arbitrary baseline has triggered a contentious pointless debate. The tax cuts enacted with the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act are due to expire at the end of this year. So extending them implies a revenue loss compared to the current law baseline, where taxes would rise significantly. Republicans have argued a ‘current policy’ baseline should be used instead. Opponents have countered that since the tax cuts were approved as temporary, they should not be built into a new baseline. Both points can be justified, but this kind of debate is totally irrelevant. What matters is where the budget deficit is today as a share of GDP, and what it will be over the next, say, 1-3 years.

A recent Goldman Sachs analysis comes to the rescue: the investment bank estimates that:

while the tax-cut package would increase budget deficits by about 0.4% of GDP compared to current policy in the next few years, tariff revenue would likely exceed that difference.

Ah, right, tariffs… It’s not that we had forgotten about them, it’s another idiosyncrasy of the budget discussions: the Congressional Budget Office treats tariffs differently. When a legislative action is proposed, like in the case of the budget bill, the CBO promptly estimates its 10-year impact. But when an executive action is announced, like tariffs, it does not. It waits until the action goes into effect, and then incorporates it into its next baseline update (slide 17 here). Tariff plans are in constant flux, which increases the confusion. But the announced across the board 10% tariff charge does not even enter the official budget discussions, which is simply bizarre.

If we go with Goldman’s estimates, the budget bill would cause a modest fiscal loosening, and with tariffs we are likely to get a marginal reduction in the fiscal deficit going forward. Not the significant reduction we need, but not a further deterioration either.

The US does have a serious fiscal problem — as do most of its peers. The way the budget debate is structured only obfuscates the issues. We need a serious discussion on how to put fiscal policy back on a sustainable path. Stronger economic growth will not do the trick if we keep running 5-6% of GDP budget deficits. We can choose expenditure reductions, which would need to include reforms to Social Security, Medicaid and Medicare. Or we can choose tax increases.

It’s a hard choice, but that’s the debate we need to have, eventually. At least now we can talk about it.

Very nice piece, Marco.

The other angle to consider is the politics of deficit reduction. If one looks at US budget deficits as a share of GDP from the 1970s to 2017, there are three instances of multi-year reductions—under Carter, Clinton and Obama.

Now that might be circumstantial rather than causal, and fiscal legislation is passed by Congress, which in many of those presidencies was divided or controlled by the GoP. Even so, matters did look different when the GoP sat in the White House, so one must wonder.

But the more important point is this: In each of those multi-year periods of deficit reduction incumbents (or their successors) reaped little, if any, political reward for their achievements. Indeed, successive Administrations (Reagan, Bush II, Trump I) happily and mostly politically successfully presided over expanding deficits (as a share of GDP) that one might argue were ‘politically financed’ by the previous administrations’ politically un-appreciated fiscal rectitude.

So while it is correct to be dismayed about how the fiscal sausage is made in Washington, DC, perhaps we must also acknowledge that we, the American people, are ultimately responsible. If election outcomes reward the politics of low taxes and high spending, then maybe we shouldn’t be all that surprised to see little progress on deficit reduction?

Which underscores your opening point, namely that we need a serious discussion about deficits.

I have a much worse opinion of the Trump administration than you have. It seems we agree that the US fiscal program - in the broad sense used in economics - is unsustainable. I am not sure however that we may all agree on this, now that the ‘bad guy’ (Trump) as opposed to the ‘good guy’ (Biden) is in power, as you seem to imply: it seems to me that Americans as so polarised that they can’t agree even on much easier to grasp economic facts (see eg the wild differences in inflation as estimated by Democrats and Republicans).

I would also like to qualify the impression you give that, possibly for the same ‘political’ reasons, public debt is now seen as a problem whereas until yesterday was seen as the solution:

- as you probably know well, and just to give examples from international institutions the economists writing the Fund’s Fiscal Monitor or the Commission’s Public Finances in Europe Report, have elaborated at length on the dangers of public debt. Political statements things may be a bit different: I understand that not everyone in the Commission is so happy with Germany throwing into the garbage their fiscal rules, not least because of the fallout on the recently reformed EU fiscal. But the dissatisfaction cannot be voiced openly, because the extra deficit spending for German rearmament is the only thing the Commission can show for the hastily conceived ‘national escape clause’ for defence;

- the big change compared to yesterday is that one may not be able to count on the interest rate on debt to be below the rate of growth of the economy and therefore to take care of debt sustainability. Until interest payments stayed constant or even decreased as share of GDP while the debt ratio kept rising it was objectively difficult for fiscal hawks to sound the alarm. The erratic behaviour of the Trump presidency is not helping in the job of selling Treasuries, I would say.