China's Three-Body Problem

The trisolar gravitational pull of geopolitical ambition, economic growth and Communist Party power might doom China to dangerous policy swings — and the rest of us with it.

Photo by Li Yang on Unsplash

The Biden - Xi Jinping meeting in San Francisco has focused attention on the fraught relationship between the two superpowers - and on China’s three-body problem.

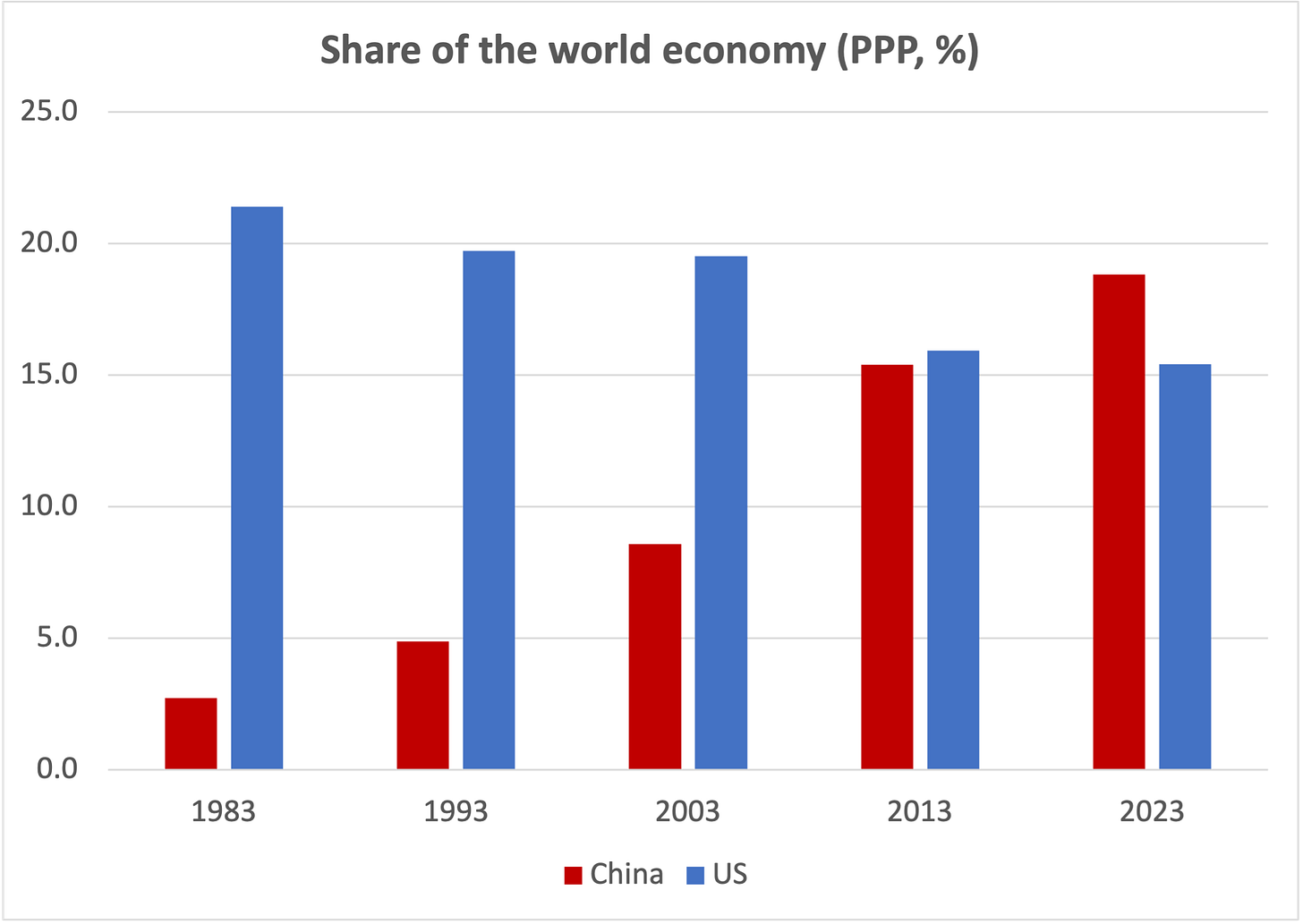

China spearheads an open challenge to the western view of the world and to the dominance of western economies and institutions. Its ambition is to replace the US as the preeminent economic and geopolitical superpower. Through a massive rapid expansion of its economy over the past decades, China has gained enormous economic influence across the world, on both emerging and developed economies. In purchasing power parity (adjusting for lower prices in China than in the US), China’s share of the world economy has already surpassed the US’s:

Source: IMF

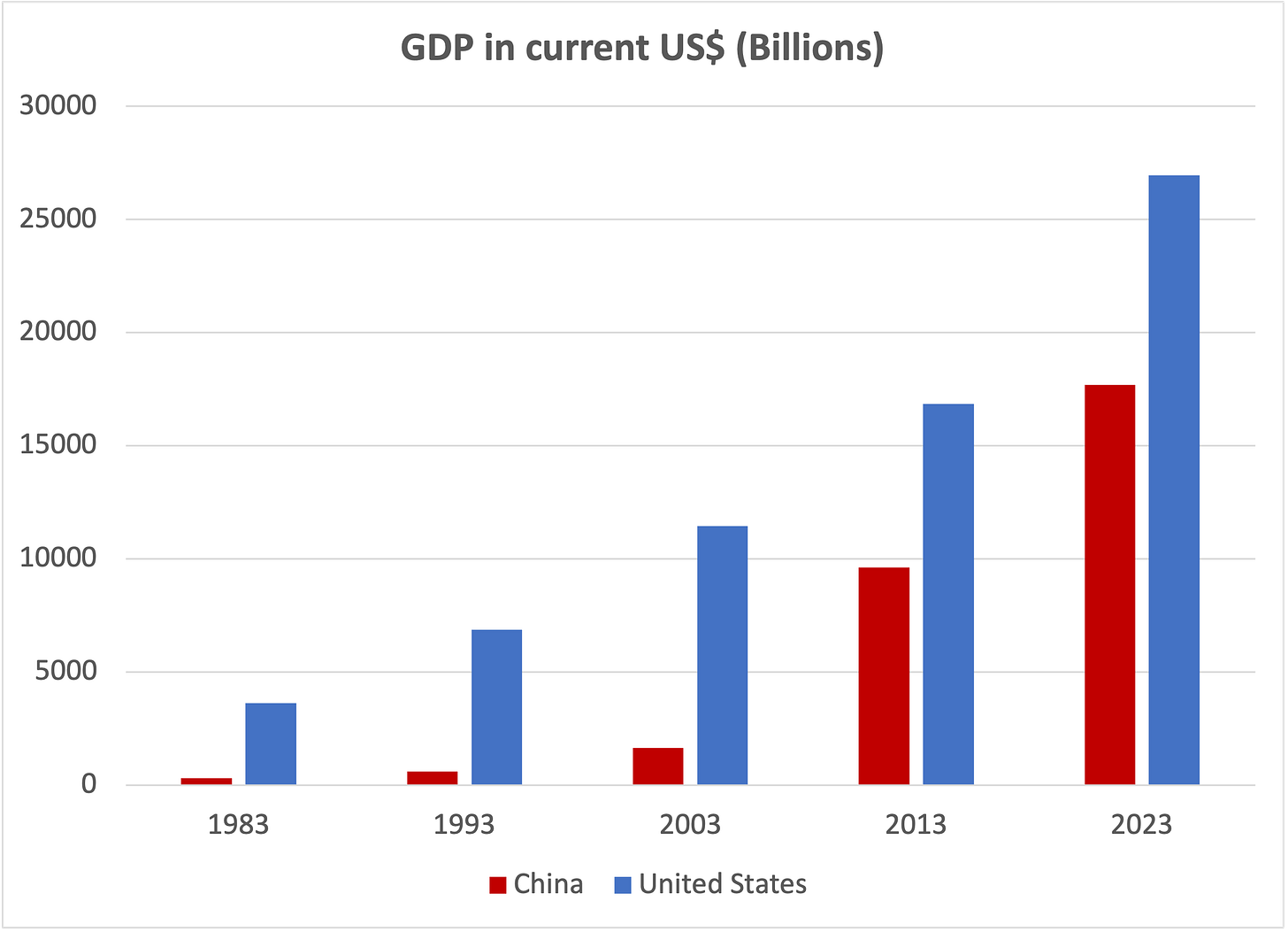

Though in unadjusted US dollar terms — most relevant for sheer economic power — the US economy is still fifty percent larger than China’s:

Source: IMF

In its geopolitical power play, China has found convergent interests with Russia, Iran and other unsavory players. With the US already engaged in supporting both Ukraine and Israel — where the risk of a larger Middle East conflict still looms — China’s strategic choices become crucial. Imagine if China decided this is the best time to make a move on Taiwan.

Bulls and bears

At the same time, most economists have turned deeply pessimistic on China’s prospects. The bearish view on China rests on two lines of argument:

First: Xi Jinping has shifted its priority from economic growth to political power. He has consolidated government control over the economy, bringing to heel the entrepreneurial leaders of China’s most successful private companies and intimidating all private players. The fast growth of a private economy was always doomed to collide with the authoritarian government system; the collision is now taking place, shattering the private economy’s prospects.

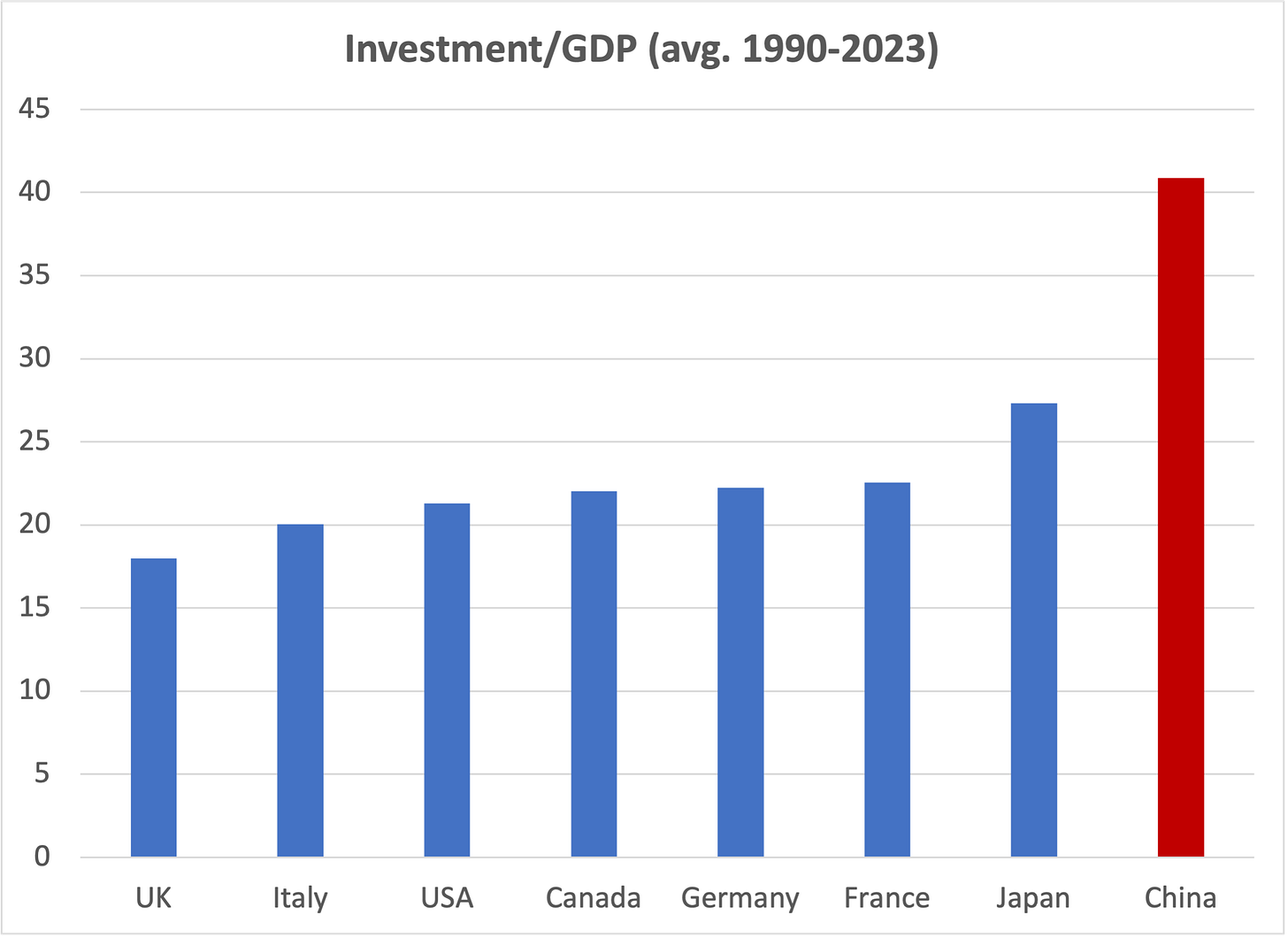

Second: Even before this political shift, China’s growth strategy was unsustainable. For too long it has relied mostly on investment and construction, while household consumption remains hamstrung by the lack of a social safety net. Michael Pettis, senior fellow at Carnegie China, made this point very cogently in a recent Financial Times article, where he notes that investment has accounted for about 40% of China’s GDP over the last thirty years; by comparison, as I show in the chart below, since 1990 investment has averaged just over 20% of GDP in most G7 countries (a bit less in the UK, and Japan’s the outlier with 27%). The share of investment in global GDP is about one-quarter, with consumption accounting for three quarters. Pettis underlines that while China accounts for less than one-fifth of the global economy, it already carries out one third of total global investment.

There are two problems with this over-reliance on investment: (a) some of it inevitably ends up being unproductive and wasteful; (b) to the extent that it is productive, and as it shifts away from real estate, it implies further strong growth in China’s manufacturing capacity, at the same time as other countries are striving to reshore and bolster their own manufacturing capacity — US included. This sets the stage for fiercer competition on global goods markets.

Source: IMF

Pettis therefore remains skeptical that China can maintain its current 4-5% growth pace without a significant rebalancing away from investment and towards consumption, something which requires tough structural reforms. (China’s aging demographic profile is another serious headwind).

Another China expert with substantial on-the-ground knowledge, Andy Rothman at Matthews Asia, has a more positive assessment. In his latest analysis, he notes that China’s consumption has been performing well, and notes that China’s policymakers are taking pragmatic steps to restore consumer and business confidence. He points to an easing of cyber security regulations, support to the residential property sector, and a shift in rhetoric in favor of the private sector. Overall, Rothman is cautiously optimistic that China can maintain its current pace of growth, though he would clearly favor a more decisive policy shift.

Love her or hate her

Assessing a country’s economic trajectory is complicated at the best of times — look at how hard it is to figure out if the US economy has secured a painless disinflation or if a recession still looms. In the case of China, the debate is complicated by less reliable data, and by the fact that for many of us it’s hard to disentangle the economic analysis from the emotional reaction — be it positive or negative — to a country that credibly challenges the US for economic and geopolitical primacy.

Pre-covid, the prevailing temptation was to praise China as manifest proof that an autocratic and centralized economic management could produce sustained strong growth. Now the wind has shifted towards the view that a communist regime was always doomed to fail on the economic front.

I think it’s too early to write off China, as many analysts and commentators are now doing.

Yes, Xi Jinping has tightened political control, including with a rather brutal handling of some sections of the private economy. But China is a diligent student of the Soviet Union’s mistakes; its leadership understands that a sufficient degree of economic liberalization is needed to keep growth going.

And I believe that China’s leadership also understands that economic underperformance would sabotage its geopolitical ambitions and endanger domestic political and social stability. After decades of fast-rising living standards, Western countries suffered a sharp slowdown in productivity and GDP growth starting on the eve of the Global Financial Crisis; this has led to a dangerous weakening of the fabric of democratic institutions: the rise of left- and right-wing populism, the increased appeal of strongmen and strongwomen, the embrace of illiberal ideologies and a much stronger tolerance for censorship and government-mandated restrictions on civil liberties. If China’s population were to similarly face a permanent reduction in growth prospects after the fast-paced improvement in living standards of the past decades, the social and political implications could be equally momentous — not something that its leadership can take lightly.

The three-body problem

This suggests that we face three possible scenarios:

China’s leadership tries to rebalance its focus towards economic growth, giving again more breathing room to the private sector. You could almost draw an analogy with the disinflation fight in the US, which started with a drastic monetary tightening to tame high inflation and now seeks the right balance to stabilize inflation at target without killing growth. China started with decisive economic liberalization measures to raise abysmal living standards; now it might seek a way to promote moderate sustained growth without endangering the party’s grip on power. This is a slow-burn strategy that would make China a progressively stronger economic and geopolitical contender — though with a high risk that economics and politics will clash again in the future.

Alternatively, China continues to prioritize political control and strangle the private sector golden goose. Growth slows even further, feeding popular discontent. China might then opt for an aggressive geopolitical play — Taiwan — to galvanize domestic support and before economic decline becomes entrenched. This scenario becomes very scary very fast.

A third scenario sees China still prioritize political power over growth, but without taking a more aggressive geopolitical stance. A China that becomes (even) more inward-looking and aims to extend its geopolitical weight only in a gradual and cautious way while its global economic weight stalls. This is the scenario many western governments would probably like to believe in.

I see the third scenario as least likely, and the first as marginally more likely than the second (always the optimist!).

But China faces a devilish three-body problem. It needs to manage the gravitational pull of three suns: the power of China’s Communist Party; domestic economic growth; and geopolitical strength.

Achieving geopolitical primacy requires stronger economic growth, which however threatens the party’s grip on power. Bolstering the CCP’s autocratic control saps the economy, undermining geopolitical ambitions. And an all-out pursuit of geopolitical goals might trigger a conflict with the US, with devastating consequences for both China’s economy and the CCP.

In Liu Cixin’s novel, the interaction of three suns condemns the planet Trisolaris to oscillate between Stable and Chaotic Eras, the latter swinging wildly between extreme cold and extreme heat. China might be similarly doomed to a cycle of sharp policy swings, with stability periodically turning into chaos.

We’re in for an interesting ride.

More readings

A couple of quick reading suggestions for the weekend: Ayaan Hirsi Ali on Why I am now a Christian, and Richard Dawkins telling her, essentially, why she is not.