Discover more from Just Think, by Marco Annunziata

ChatGPT, Productivity And The Great Cognitive Challenge: Seven Lessons And Three Calls To Action

AI leaps forward, productivity lags behind. The biggest risk does not come from AI; it comes from our temptation to let our cognitive abilities waste away.

Image generated with DALL-E

Artificial Intelligence has taken a great leap forward. ChatGPT is all the rage, and image generators like DALL-E are entertaining vast numbers of people, sometimes with impressive results. META’s Cicero AI agent now excels at Diplomacy, a strategy game centered on a quintessentially human strength: our ability to win others’ trust, and betray it.

Reactions, predictably, have been polarized. Enthusiasts say we are witnessing game-changing innovations that have finally brought us to the very brink of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) — an AI that is no longer just good at highly specialized tasks, but that can master any intellectual challenge that humans can.

Skeptics counter that these new programs are just glorified plagiarists which copy and paste images, words and thoughts already created by humans. ChatGPT in particular has been shown to be terribly unreliable: the answers it delivers sound perfectly plausible and entirely convincing, but you can’t ever be sure if they are true or completely made up.

Productivity paradox 2.0

The skeptics can also cite the Solow paradox. Back in 1986, surrounded by mounting enthusiasm for the new power of computers, MIT economist Robert Solow drily observed, “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” For all the hype, productivity in the US and other advanced economies languished at pitifully low rates of growth.

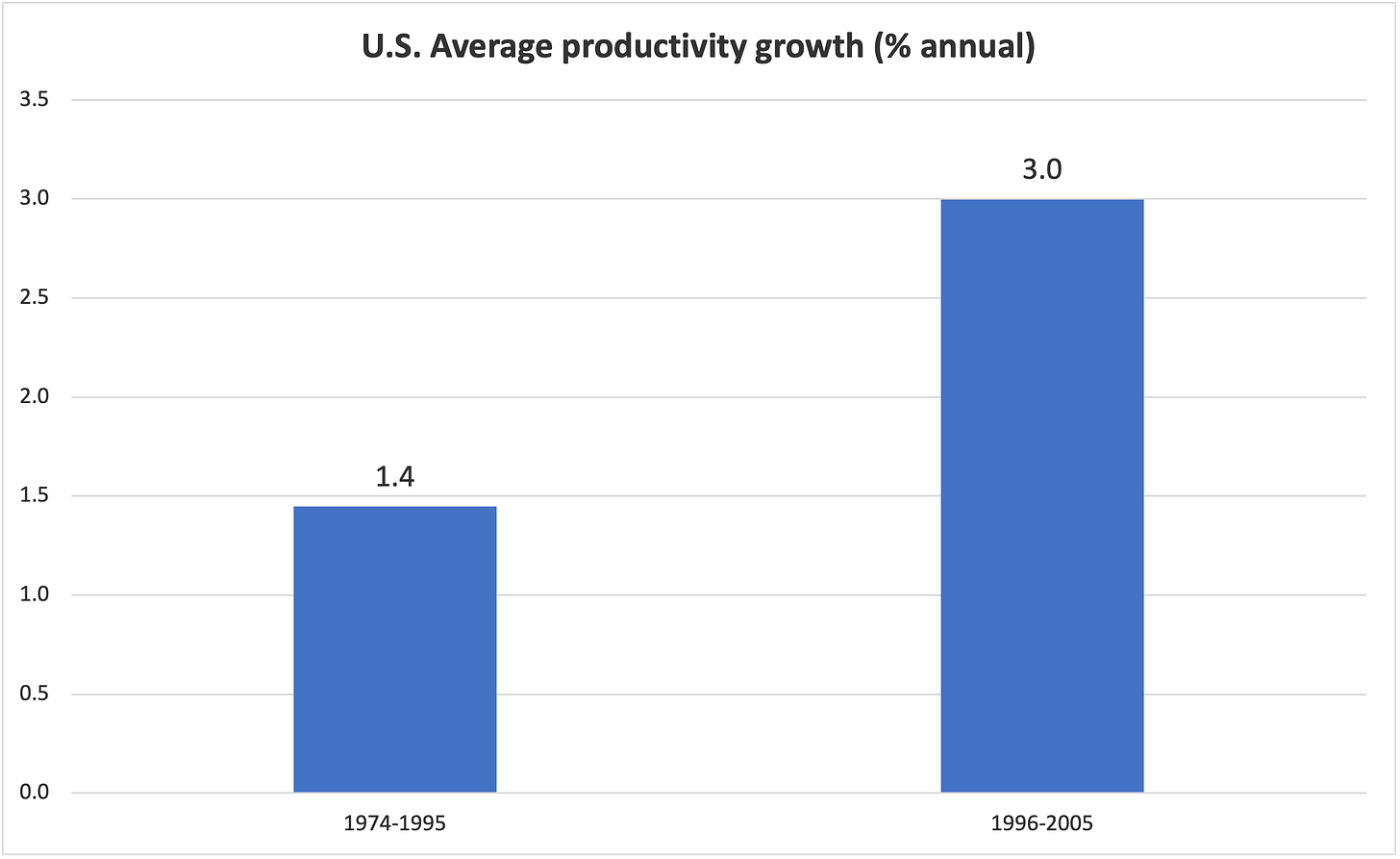

Ten years later, however, productivity surged: in the US, between 1996 and 2005 it grew at an average of 3% per year, more than double the pace of the preceding two decades. Academic studies ascribe that productivity surge to the Information and Communications Technologies revolution spurred by computers. It had just taken time for companies to learn how to take advantage of the new technology, adapting processes, management strategies and incentives.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

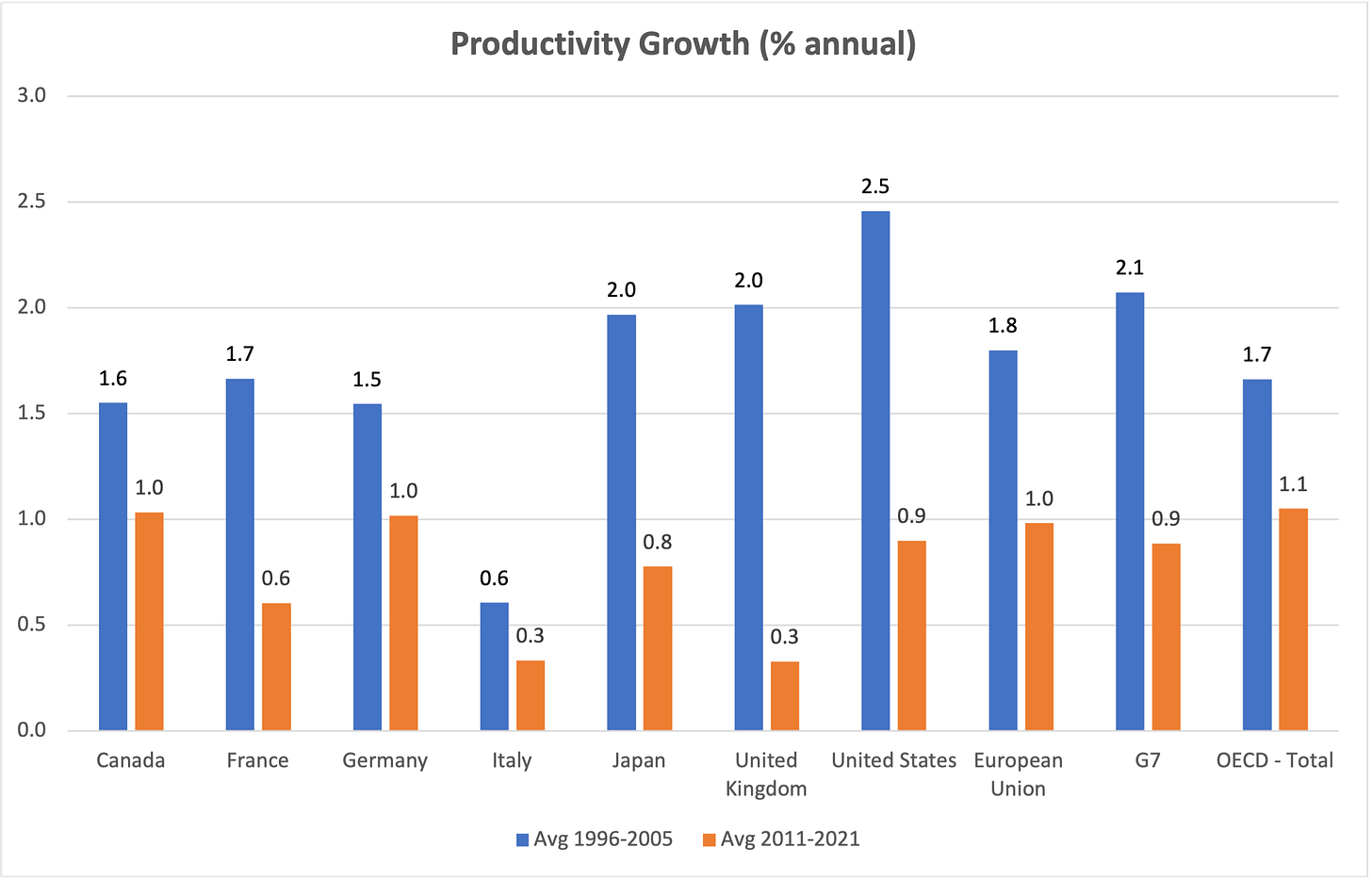

Today the Solow Paradox is back. Productivity growth has slowed to a trickle. Across the G7, average productivity growth since after the Global Financial Crisis is less than half of what it used to be in its golden age. In the US it’s fallen to almost one third of what it used to be. In the UK and Italy it has essentially ground to a halt.

Source: OECD

What have you done for me lately?

So, what have you done for me lately? What good is this innovation if it can’t accelerate the rise in living standards?

If we have gotten within striking distance of AGI, we should see some truly revolutionary benefits. A cure for cancer, or for Alzheimer, or any other of the crippling diseases that we’ve been fighting unsuccessfully for decades. A new source of clean, cheap abundant energy. A surprisingly creative solution to climate change. Learning yet another board game or rendering a bespectacled dancing squirrel in the style of Salvador Dali does not quite cut it.

Are we about to be as surprised as Solow was, within as little as a decade? Or will the new wonders once again be limited to games, social media and disinformation?

Seven lessons

Here are seven important lessons we should draw:

We should think harder about what it is that we humans really do better. We complain that image generators like DALL-E just imitate and mix already existing styles; but so do most human artists and architects. We all draw inspiration from what our peers have done or are doing — and only rarely someone comes up with a remarkable break from tradition. ChatGPT researches and assembles existing text; but so do most of us when we do research. The crucial criticism of ChatGPT, well-articulated by Professor Gary Marcus, is that it does not understand what it is reading and writing because it lacks a mental model to understand it. True, and this goes to the heart of the long standing debate between symbolic and machine learning approaches to AI. But many of us don’t understand what we read either, and also come out with the wrong answers.

By producing output that is so convincingly human-like, programs such as ChatGPT and DALL-E will force us to think much more seriously about what intelligence is, and whether and how we can reproduce in silicon software the “wetware” of the human brain.

These latest AI solutions provide a new playground for human-machine collaboration. It has quickly become clear that the best results in both image and text generation come when the human user engages deeply with the AI, providing detailed and structured prompts and giving feedback, directing changes and iterating. (Professor Ethan Mollick provides some powerful examples from his innovation and entrepreneurship classes at Wharton.) This is something we had already witnessed in the field of generative design, where humans have had to gradually learn how to co-create with the AI.

The ongoing challenge is to learn how to use these new tools — and see whether they are really transformational or not. Whether they can help us achieve new and better results or not. My sense is that the answer will be yes, but the improvements will be incremental, not transformational. Because we are still way too far from anything resembling AGI.

Where we apply these innovations matters. They continue to go first and foremost in social media, entertainment and advertising (including of course the porn industry). Why? Mostly because that’s where the money is; and partly because they lend themselves so well to these data-rich environments. That’s not a failure of innovation, it’s a failure of our economic system. If we don’t fix it, improvements in AI will continue to be tailored to the priorities of these industries, and we should not be surprised if productivity keeps languishing and social dysfunctions like disinformation and political polarizations get worse.

The impact these new technologies will have on our attitudes and cognitive abilities will be crucial. Computers and calculators are phenomenally useful tools; but a growing majority of people in many advanced economies have allowed their mathematical skills to atrophy — in some cases never really bothered to acquire them — and this has not resulted in a surge of unprecedented achievements, quite the opposite. Remember the dismal productivity statistics in the chart above.

Digital technologies leveraged through the perverse economic incentives of social media and advertising risk bringing about a Great Cognitive Depression — as Mickey McManus and I warned in a joint article. ChatGPT fits well into that picture. Yes, it can be a powerful research ally. But in the US we already have a large proportion of kids who struggle to acquire basic reading and comprehension skills — partly due to the disastrous extended school closures during the pandemic. Give these kids access to ChatGPT, and how do you think they will use it? Most likely as a convenient replacement for basic skills that will continue to atrophy. The biggest AI risk does not come from programs like ChatGPT. It comes from us. From how we will be irresistibly drawn to anthropomorphize an AI that speaks like us and to rely on it as an easy lazy option to get all the answers without doing any of the work — and without bothering to check if the answers are right or wrong. Artificial Intelligence is no match for human stupidity.

Three calls to action - The Great Cognitive Challenge

I will conclude with three calls to action, three simple principles we should follow in embracing — or coping with — this new phase of AI advances.

First: Don’t expect miracles, but try to understand how these new AI tools work and how we can best use them to solve problems that have so far eluded us;

Second: Learn to collaborate with the machines, use the technology as a teammate, not a crutch;

Third: strengthen human skills, starting with the good old traditional skills in the school system and then developing the abilities that can make us most successful in leveraging these new tools.

We face a Great Cognitive Challenge; we’ll be tempted more and more into the easy choice of asking the machines for answers and letting our cognition fall into a deep sleep, into necrosis. We must resist it, and work harder at making our cognition better and stronger. Otherwise the productivity paradox will morph into a depressing inevitable reality of economic and intellectual stagnation.

Subscribe to Just Think, by Marco Annunziata

Stepping away from groupthink, with a focus on economics and innovation